I listened intently as Professor Maria Pia Paganelli explained the opening chapters of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations at the Common Sense Society’s Caledonia Fellowship in Scotland. It hit me with full force that the Scottish Enlightenment thinker’s work was not a defense of selfishness, but motivated by sympathy for the most helpless members of society.

Lord Rockville, Mr. Adam Smith & Commissioner Brown, John Kay, 1787. British Museum.

At the same time, I was vaguely aware of a connection between Smith and the constitution of my home country, Norway – a connection that I became determined to investigate. It turns out that Adam Smith and also his friend and admirer, the Irish statesman Edmund Burke, may have had a real influence on the men who met in 1814 to create a new constitution for an independent Norway.

In 1759, Norway was still in a union with Denmark. The Norwegian Anker family, who were wealthy timber merchants, decided to send their sons on a “grand tour” of Europe. There was the 18-year-old Peter Anker and his 15-year-old brother, Carsten Anker, as well as their tutor, Andreas Holt.

One of the many cities they visited in Great Britain was Glasgow, where Adam Smith was a professor of moral philosophy at the university. The brothers received a warm welcome and were even made honorary citizens. Smith himself spoke to them, and was kind enough to write a greeting in their travel diary, dated 28 May 1762:

I shall always be happy to hear of the welfare & prosperity of three Gentlemen in whose conversation I have had so much pleasure, as in that of the two Messrs. Anchor & of their worthy Tutor Mr. Holt.

After Glasgow, the brothers came to London and met their cousins Jess and Peder Anker. The late Professor Preben Munthe of the University of Oslo has argued that the brothers would have shared enough information from their meeting with Smith, who had already published his Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759, to influence their cousins’ way of thinking about society.

Illustration of the Royal Frederick University in Christiania, the original name of the University of Oslo, 1873. Wikimedia.

Two years later, Peter and Carsten met Smith again in Toulouse, France. At this point, he had begun writing the Wealth of Nations – “in order to pass away the time,” according to a letter he wrote to David Hume. The brothers undoubtedly learned much from him before returning to Norway. Interestingly, Smith later expressed his skepticism about the grand tour concept, observing:

A young man who goes abroad at seventeen or eighteen … commonly returns home more conceited, more unprincipled, more dissipated, and more incapable of any serious application either to study or to business, than he could well have become in so short a time had he lived at home.

Smith blames “the discredit into which the universities are allowing themselves to fall” for bringing “into repute so very absurd a practice as that of traveling at this early period of life.” It should, however, be remembered that Norway did not have a university of its own at this time. The University of Oslo was only founded in 1811, although many would travel to study in Copenhagen.

In 1779, Holt and the brothers were involved in translating and publishing Smith’s Wealth of Nations in Danish, the language used in both Denmark and Norway at the time. Smith expressed his gratitude and wrote of “the distinguished honour” he felt. The translation allowed his ideas to reach a wider audience, and perhaps to help end a Danish trade monopoly in Iceland.

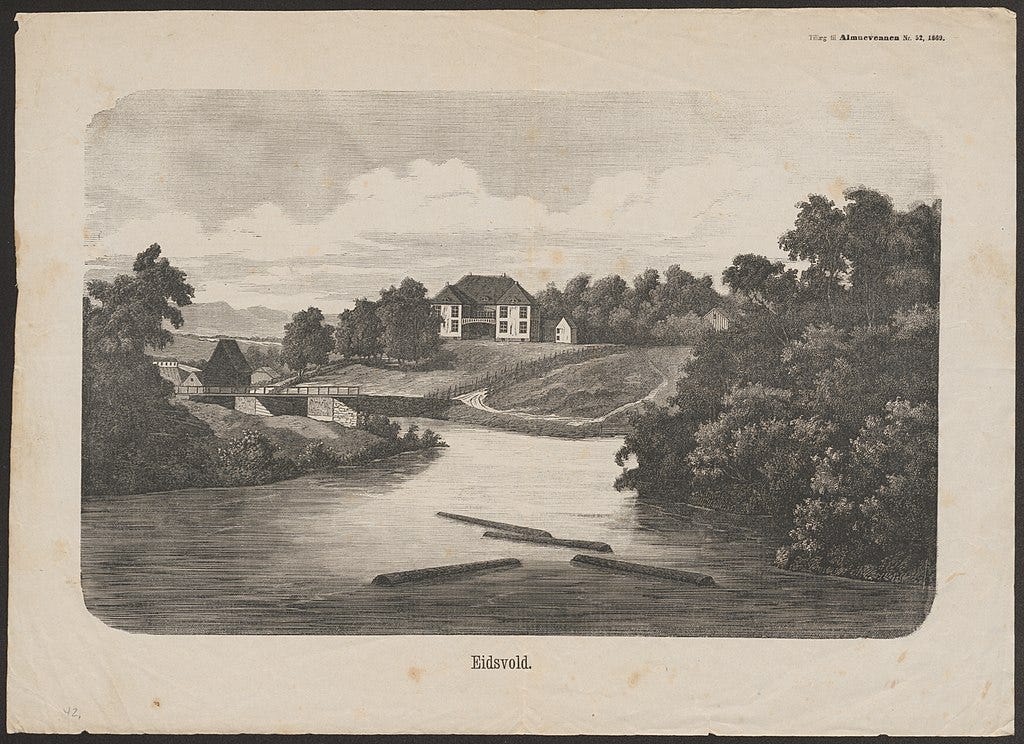

Eidsvollbuilding. Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage/Wikimedia.

Peter Anker became governor-general of the Danish-Norwegian colony at Tranquebar in India. He also participated in a meeting to prepare the Norwegian Constituent Assembly in 1814. Carsten Anker became a civil servant, owner of the Eidsvoll Ironworks and convenor of the aforementioned meeting. He was not present during the creation of the constitution, but lent his manor house at Eidsvoll for that purpose.

One of their cousins, Jess Anker, may have read a 1790 essay in the Minerva magazine about the Reflections on the Revolution in France by Edmund Burke. This could be what led him to buy a first-edition copy of the book, which was found among his belongings. Although Jess was the family’s black sheep, it is possible that they would listen to him and his Burkean views of the French Revolution.

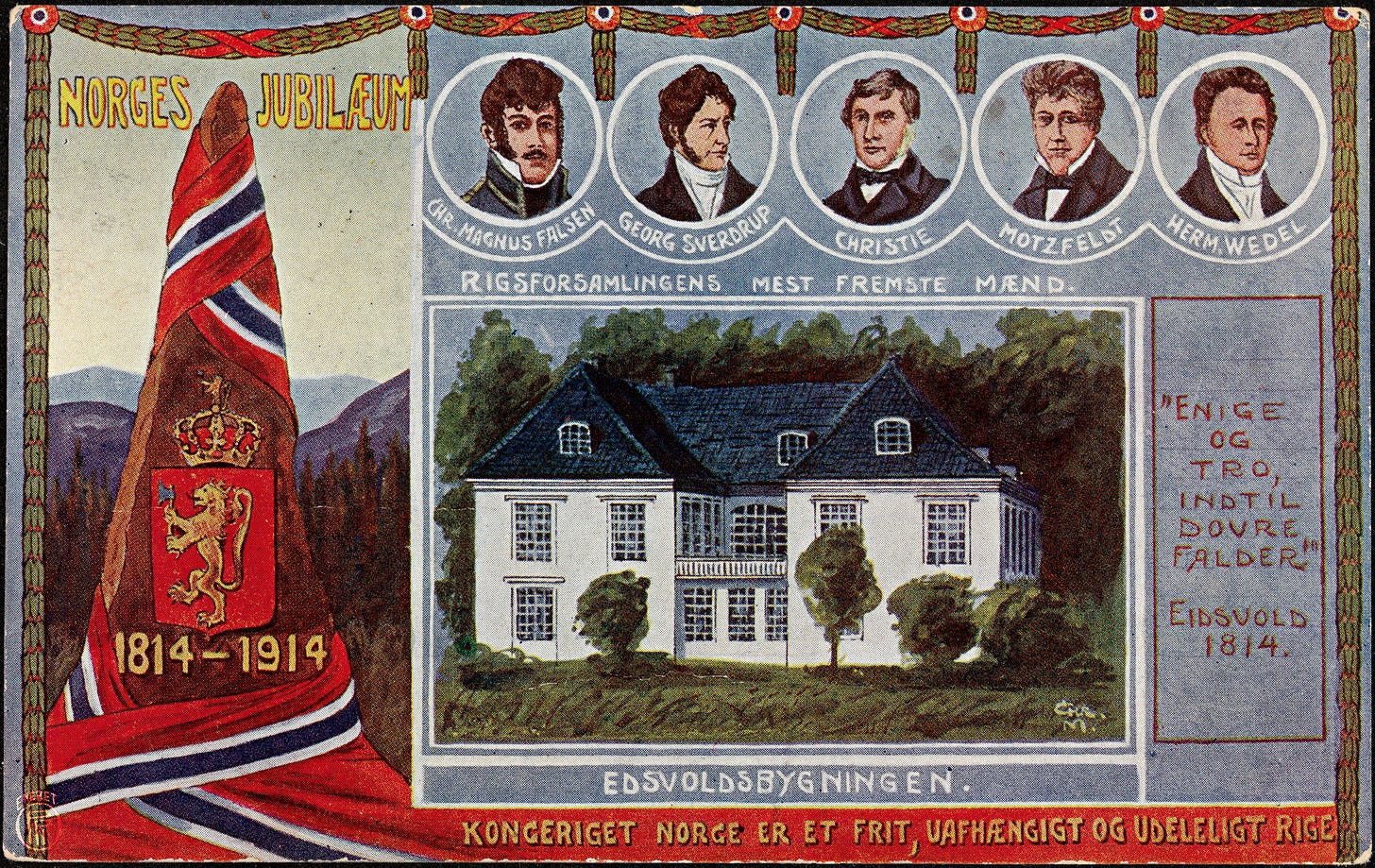

Jess’ brother, Peder Anker, was one of 112 men who took part in the Constituent Assembly at Eidsvoll in 1814. He was undoubtedly one of the most influential. In the list of signers of the Norwegian Constitution, the first name – even before Christian Magnus Falsen, the “Father of the Constitution” – is Peder’s. The signing took place on 17 May, a day we now celebrate as our Constitution Day.

Is there any trace of Adam Smith’s ideas in the Norwegian Constitution? Professor Munthe argued that there is, in § 101: “New and constant restrictions in the liberty of trades must not be allowed to anybody for the future.” This free-trade paragraph was directed towards the Danish-Norwegian system of mercantilism, under which only some merchants were granted special privileges by the king.

Christian Magnus Falsen and other important Eidsvoll men on a patriotic postcard, Christian Magnus, 1914. National Library of Norway.

As a whole, the original 1814 Constitution places some restrictions on government power. It states that nobody may be punished without judgment or detained without sanction in law, and that “liberty of the press shall take place” (§ 100). It upholds a right to private property in general and the ancient “Odels- and Aasædes-Ret” – the “right of redeeming patrimonial lands and of dwelling on the chief mansion” (§ 107) in particular.

Smith should not perhaps have been so quick to dismiss the concept of a grand tour. At least partly due to his meeting with the young Anker brothers in the mid-1700s, some of Smith’s ideas found their way into the constitution and civil service of Norway. His friend, Edmund Burke, was known in Norway through the influence of an Anker cousin. Anyone who wishes to promote their work in this country can point to that legacy.