America’s Burke

Crusty New England lawyer and statesman John Adams offers a foundation for American conservatism

Conservative Americans have always been at a political disadvantage. English philosopher Edmund Burke, the greatest defender of tradition and prescriptive rights never set foot on American soil. And the American political tradition, which rests on the premise that government can be crafted from the ground up through “reflection and choice,” generally opposes revolutionary and ideological forces. In short, traditionalist Americans are seemingly bereft of a thinker who can help them recast a political tradition that on the surface appears boldly rationalistic. Fortunately, however, fortune has not abandoned these conservative Americans. Crusty New England lawyer, statesman, and one-term president John Adams offers a serious political teaching that can provide a foundation for American conservatism and lessons for our modern age. Adams believed that human beings were marked by decidedly low character. This premise led him to conclude that long-term human progress and utopias were impossible. In his eyes, improving one’s lot in life required balanced government and the cultivation of personal virtue rather than dreams of a radically transformed future. His understanding of government has great potential to teach modern-day conservatives how to better direct their own political movement.

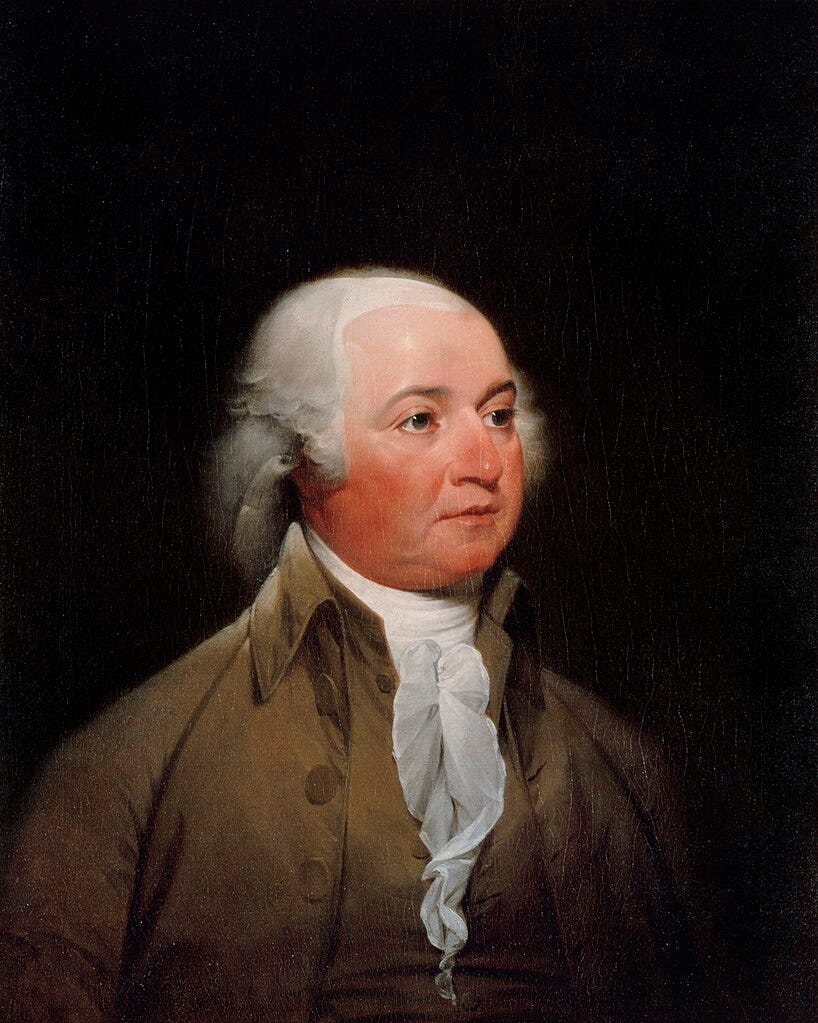

Official presidential portrait of John Adams. John Trumbull circa 1792. The White House.

Adams grounded his political thought in a belief in man’s fallen nature. He rejects the Enlightenment’s hopeful vision that assumes scientific progress guarantees human progress. Instead, he argues that society’s increasing knowledge has worked merely to further release the pernicious passions of man. Adjusting government under the expectation that it would improve correspondent with human progress is as likely as entering the age of “dragons, giants, and fairies.” In Adams’s view, human nature is inflexible and man “is as incapable now of going through revolutions with temper and sobriety, with patience and prudence, or without fury and madness” as it ever was. Reason will never rule the general populace because they are incapable of overcoming selfish desires.

Adams answers this depressing picture of our own nature with a firm belief that strong political institutions and virtuous citizens can curb our excesses. Constitutional restraints serve the dual purpose of preventing political officials from abusing their power and preventing the voting populace from tyrannizing over their opposition through a representative majority. Adams contends that government will always descend into “a state of anarchy and outrage” without constitutional institutions that check and balance power and restrain the people. Only the establishment of constitutional institutions and procedures can preserve the “people’s rights and liberties.”

At their very best, these constitutional restraints were composed of multiple competing parts that balanced society’s aristocratic and democratic elements, since neither group could be trusted with exclusive political power of their own. In Empire of Liberty, historian Gordon Wood argued: “Nothing but force and power and strength can restrain them [the selfish passions]. Nothing but three different orders of men, bound by their interest to watch over each other and stand the guardians of the law” will maintain peace.

The execution of King Louis XVI, by Charles Monnet, engraved by Isidore Stanislas Helman, 1793. Wikimedia.

Restraining society’s competing interests through political institutions, however, does not guarantee a healthy regime. Equally vital to a regime’s success was a vibrant and virtuous citizenry, cultivated through religion and strong liberal arts education. He contended that “the happiness of the people, and the good order and preservation of civil government, essentially depend upon piety, religion, and morality” and that state governments must establish and encourage their citizens’ religiosity. As the primary author of the Constitution of Massachusetts, Adams provided for congregational churches to be funded through state assistance. Adams advocated religious tolerance, but he had no patience for the propagation of atheist philosophy that he witnessed in France. The average human beings’ morality would wither away, he suspected, without firm belief in God.

Adams believed that citizens’ morality would also be cultivated through a strong educational system. Schools would teach citizens to read and think seriously about moral questions, and thereby overcome their own selfish nature. Like most Christians of his time, Adams thought that self-improvement was a challenge; individuals had to strive to become virtuous; and this task was impossible without serious self-reflection. Adams believed that great books and natural history were the catalyst for self-reflection; through study, citizens could master their vices. “The whole people must take upon themselves the education of the whole people,” he argued, “and must be willing to bear the expenses of it. There should not be a district of one-mile square without a school in it.”

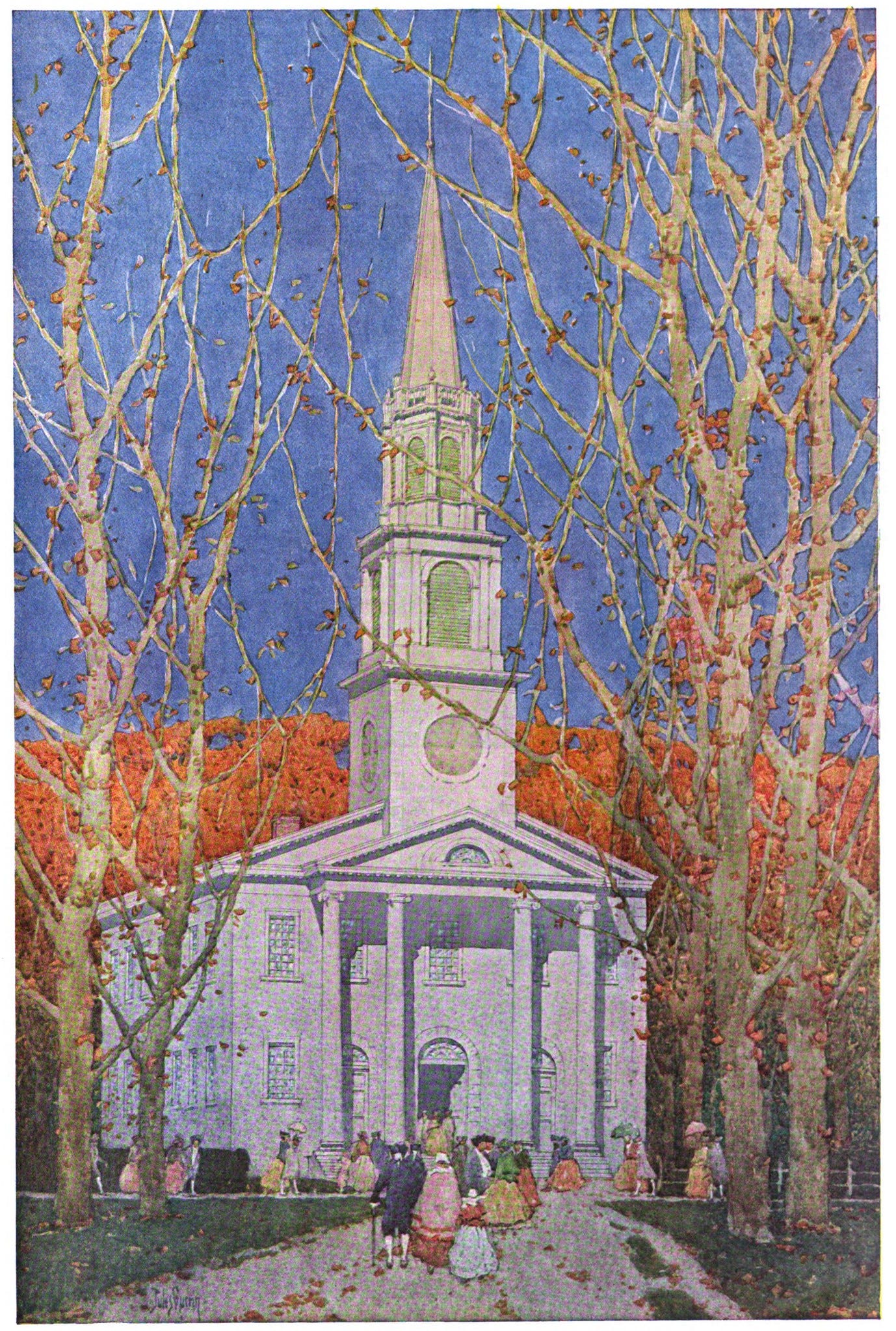

Magazine illustration of Christians attending church. Public Domain TheCMN/Flickr.

Conservatives could learn a great deal from John Adams’s political thought. His deeply held Christian moral sense that sees man’s nature as fallen, but redeemable, sits at the heart of the conservative disposition. His twin solutions—constitutional restraint and morality—are strong answers to the eternal problem of how to form a good regime. Adams’s sober, pragmatic conservatism may not be especially hopeful or populist, but it has always rested at the core of the philosophy and is always worth reviving.