ANZAC Day: The First World War and the peculiar virtue of Australian Friendship

One of my mother’s favorite photographs is one she’s never seen. It was taken on April 25, 1995, in the pre-dawn calm, on the Esplanade, in Cairns, Tropical Far North Queensland, Australia. We were there, at the Cenotaph in my hometown, where thousands had gathered to pay their respects to the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) fallen. War has never visited Australia in earnest, but our best men have for over a century been sent abroad to die for causes great and good. These venerated dead were our hardy men of Imperial legend, the men upon whose shoulders it seemed to me all Australian greatness was built. “Lest we forget,” is the refrain we speak in their honor, as by tradition, we gather in the pre-dawn hours. Perhaps, we think, by assembling at the same dark hour those heroes first went ashore in war-torn Europe, we might better meditate on the nature of their sacrifice.

On that morning—the first dawn service I ever attended—8-year-old me wandered up to the war memorial and cast wandering eyes over its modest provincial obelisk. I gazed up at the heroic Smiths, the Joneses, the Mc-somebodies, and the O-someones recorded for posterity—their names receding from granite to still black sky. Those were names from an Australia I knew well but was already changing rapidly. It was a country Irish in blood, South Asian by geography, but halfway American and English by political sensibility. Of course, it was also home to the oldest indigenous culture in the world, but we didn’t hear too much about Aboriginal soldiers back then—even the ones who’d picked up rifles and fought alongside the colonial settlers. It baked in sunlight, toiled on dusty open plains and greasy closed factories, and leisured gloriously on coastlines of inestimable natural beauty. Watching me stare, a news photographer saw the moment and asked if I’d hold my gaze a little longer. She took one precious shot on scarce film. My mum knew that the shot would be memorable. The next week she hurried down to buy a copy at the Cairns Post’s offices. When she arrived she found one dud negative right where the memorial and I should have popped up in the morning’s storyboard.

Trivial events can anchor memories. Wondering about that lost photo is tied up with my first memories of ANZAC Day. I imagine most Australians have similar memories—admixtures of novel excitement, earnest gratitude, and faintly apprehended national pride. I imagine also, that as childhood gives way to adolescence gives way to adulthood, that each and every person raised on Australian shores watches their relationship to this hallowed day change—sometimes perplexingly—over time. In the tiniest towns we come to empathize with the widow’s solemn dignity. In our classrooms we become outraged over the needless loss of life. In our biggest cities we thrill to the sound of marching bands ricocheting imperious strains off imperious colonial buildings. We look up and see yet more imperious squadrons menacing the skies. But we remain perplexed: how did we come to live in a country that celebrates the tragic and exalts the futility of a battle waged on foreign lands for foreign masters?

Being perplexed is part of the nature of growing up, but it is also part of the difficulty of reasoning with the nature of ANZAC Day. Though roughly equivalent, ANZAC Day is not the same for Australians as July 4th is for Americans, or Bastille Day is for the French. It is not like St. George’s day for England, or St. David’s day for Wales. It is certainly not like St. Patrick’s Day for Ireland, although by cool evening’s light in the laneway pubs of old Sydney it looks and sounds about the same, albeit with more uniformed folk among the patrons. We have our official national day too, January 26th, the date the first British fleet landed at Sydney Cove in 1788. But we fight about January 26th now. We don’t, however, fight about ANZAC Day: it is wholly sacred.

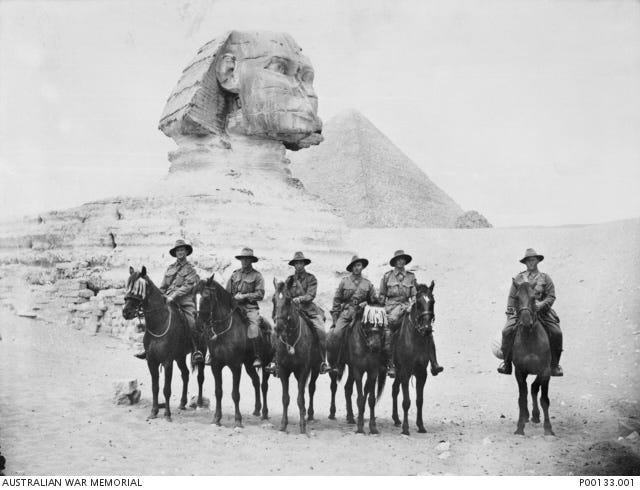

In simple terms, April 25th is Australia’s most solemn day of remembrance. It commemorates the moment at which a national Australian presence entered the First World War. On that day in 1915, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps landed upon the shores of the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey. The landing was part of the disastrous Dardanelles campaign—a campaign orchestrated, ironically, in large part by Winston Churchill, the man who in the next great global conflagration saved the world from tyranny. It is a day modern Australia now acknowledges as marking its spiritual birth, if not its legal and material one.

The simple bravery Australia’s soldiers displayed in the First World War is contrasted by the complex circumstances that gave birth to the ANZAC legend: It is ANZAC Day on which we Australians most ardently celebrate securing our national freedom—yet no tyrant from that era ever threatened our own shores; it is ANZAC Day around which we instinctively know Australian nationhood catalyzed—yet on this day our men fought under foreign command, fed into trenches as cannon fodder by an alien aristocratic officer class; and it is ANZAC Day on which we celebrate the triumph of our great, new, and youthful continental nation—yet this was not a day of victory. On April 25, 1915, the best men of our idyllic pacific paradise were spat onto gruff northern beaches to meet the dreadful fiery metal of the Old World in its sunset.

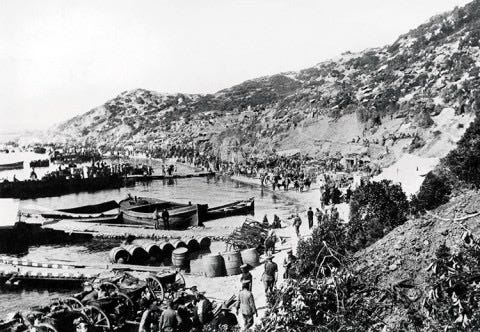

The first men came ashore from His Majesty’s ships—the HMS London, the HMS Queen, and the HMS Prince of Wales. If Australian soldiers needed any more proof of their identity paradox, they needn’t have looked further than the boughs of their own vessels. Not fifteen years after its Federation (the Australian constitution was ratified on July 6, 1900), Australia’s men were delivered to battle for their mother country, conscripted onto ships bearing totems of Empire.

Upon landing, the ANZAC were shredded by Turkish machine gun fire spitting relentlessly from fortified high ground. Scores died on the beaches, and the British Imperial forces would never substantially advance beyond their landing positions. At least 650 men died in the landing alone, with the final tally unascertainable: the battlefield’s chaos prevented recovery of the dead for days, if not weeks at a time.

The slaughtering Turks came to revere the ANZAC’s courage. Today, the beach upon which they landed is named “ANZAC Cove” in tribute to the selfless Australian and New Zealand soldiers who poured from ships and attacked terrain more forbidding and hopelessly unattainable than any sane man would brave. Gallipoli’s foreboding cliffs made Normandy’s beachhead look like a cakewalk.

At first, the Australian public was fed news of the mission’s “success.” But gradually the tragedy’s reality trickled home. Fathers’ pride at boys’ adventure gave way to mothers’ grief at apprehensions vindicated. Families were decimated. Pre-war Australia’s cultural and economic strength was its nascent pastoral excellence. Great Australian families who had pioneered the sheep runs west of Sydney and north of Melbourne, opening up the engine room of the Australian economy, watched in horror as the sons they’d counted on working their land were buried in a foreign one. The wool they’d once sent to Europe—the world’s finest—was supposed to make the country rich, but instead it lay calamitously perforated by enemy bullets.

I went to the First World War memorial in Pershing Square, Washington D.C. last week, where my fellow Australians gathered in their hundreds (as they do on this day all over the world) to mourn the ANZACs. As the slow-rising sun warmed the pavement on Pennsylvania Avenue, Australia’s ambassador to the United States, Kevin Rudd, explained to American dignitaries how Australia’s habit of exalting its greatest tragedy may be perplexing to other nations. Rudd is from Nambour, a small town at the other end of Queensland, my home state. In 1915, a train dubbed the “March to Freedom” traveled half that state’s length, stopping in Nambour and picking up excited young men with a promise to have them home soon. It seems innate to the Australian character, Ambassador Rudd reflected, to know the paradox of honor earned in tragedy.

This paradox reminds us that for Australians, there is no simple path to patriotism. The collision of fortune and circumstance that bestowed the Americans, our fellow travelers in the new world, with the agency to boldly define the terms of their arrival in the community of nations, never happened in Australia. Politics never gave us the time in national fermentation so potently admitted of our motherland, Great Britain. Geography never gave us the benignity of the remotest outposts of Empire, and demography never gave us insignificance or obscurity enough to escape the gravity of the European historical vortex which claimed to ignore us, but drew us callously into its stupid calamity, regardless.

These problems, the futilities of Australian identity at war, are part of ANZAC Day’s essence. They point to an uncomfortable vulnerability in assessing the birth of our nationhood in a moment of utter tragedy, in lieu of what I’m sure we would prefer was profound triumph. But again, paradoxically, they also allow Australians to apprehend patriotism of an uncommonly high order.

When a man’s cause is not his own, when a man must fight to defend his country in the abstract, and not for the sake of its own soil, when he realizes that the leaders ordering his sacrifice are not of his own flesh and blood, then what more can he fight for than the love of the one who stands beside him?

This, the Australian love of friendship, was the true national discovery the ANZAC soldiers made at Gallipoli.

Since that day, friendship has been the essential virtue of Australian patriotism. This is something we come to understand as we reckon with the Gallipoli tragedy and come to find in it the peculiar genus of Australian greatness. This is why, I am sure, when former Prime Minister John Howard pushed the ANZAC tradition to the fore of public consciousness in his twelve years in office, the term, “mateship” made a welcome return to Australia’s national vernacular.

Among the world’s military powers, Australia is the most famed for its friendship among allies. Australia is the only nation to have fought at the United States’s side in every major conflict since the First World War. And in that war, the U.S.’s first combat operations under a foreign commander were directed by the great Australian general, Sir John Monash. Monash, as a gesture of honor, famously set the battle date for the two countries’ joint assault at Hamel, France, for July 4, 1918. In turn, the Americans proclaimed they would sooner wear Australian uniforms than those of any others. Monash later wrote that the Americans “were ever after received by the Australians as blood brothers.” This manifestation of “mateship,” first between men, and then between nations, is a direct legacy of the ANZAC tradition born of war.

This is surely also why the great director Peter Weir, when creating his masterpiece Gallipoli, made his film at its very heart, not about war, but about friendship. Galipolli’s two protagonists, Frank Dunne (Mel Gibson) and Archie Hamilton (Mark Lee), capture the essential nature of Australian mateship. It is this essence which lies at the heart of Australia’s national identity. I have said many times that one cannot truly understand that movie, cannot understand the spirit that animated the Gallipoli campaign, and cannot truly understand the nature of Australia, until they have experienced a truly great friendship.

That is why I say that Australians have no easy path to patriotism, and why our relationship to the ANZACs changes perplexingly over the course of our lives: friendship is difficult. It is beset by betrayals both grave and petty, it is misunderstood in childhood, distorted in youth, and for some, can be chimerical in adulthood. But its capacity for self-recognition remains an intrinsic feature of the Australian disposition. Long may it continue to be, and long may we venerate the ANZACs themselves, those great men who seared friendship’s virtue into our nation’s soul.

Lest we forget.