How A Stone Slab With A Boring Inscription Unlocked The Pharaohs’ Secrets

After decades of hard translation work by Europe’s scholars, the stone uncovered ancient Egyptian history

Ancient Egypt has always fascinated the world. The pharaohs’ magnificent wealth, the pyramids and other colossal monuments, and the civilization’s tremendous longevity captivate the imaginations of generations. But without the discovery of an unassuming slab of rock whose full importance was deciphered 201 years ago this September 27th, we would know little to nothing about the land known as the “Gift of the Nile.”

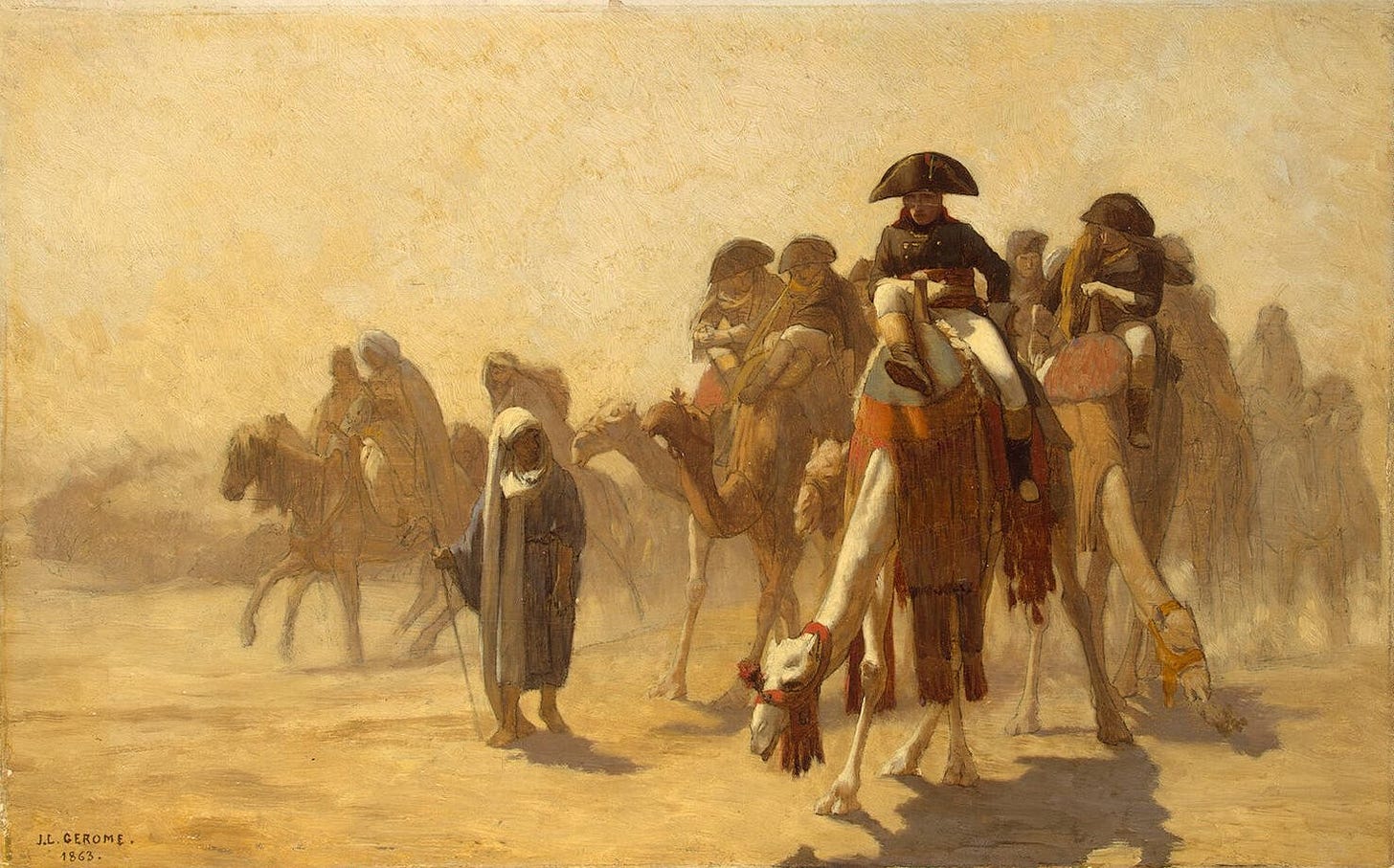

General Bonaparte with his Headquarters in Egypt, Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1863. Hermitage Museum/Wikimedia.

The Rosetta Stone was unearthed by accident. In 1798, Europe’s monarchs were attempting to crush the nascent French Revolution. France’s best general and future emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte, invaded Egypt to use it as a springboard for an expedition he hoped would reach India, where he could disrupt the interests of France’s primary enemy, Great Britain.

During this invasion, while setting up a fort close to the town of Rosetta (or Rashid), a French lieutenant named Pierre-François Bouchard uncovered a large stone block engraved with strange writing. Written on the Rosetta Stone, as it came to be known, was a single text in two languages and three different alphabets: Egyptian hieroglyphics, ancient Greek, and Demotic (an Egyptian script for day-to-day usage).

Understanding the magnitude of his discovery, Bouchard quickly sent the stone to Cairo so the hundreds of scholars that Napoleon brought with him could study it. The British eventually defeated the French in Egypt and took the Rosetta Stone back to Great Britain, where it still resides in the British Museum today.

Experts inspecting the Rosetta Stone during the International Congress of Orientalists, Illustrated London News, 1874. British Museum/Wikimedia.

The Rosetta Stone’s discovery started an international race to see who would be the first scholar to translate its text. Because Egyptian hieroglyphics had not been used since the fourth century A.D., deciphering the text was a difficult task requiring decades and many scholars working together. The British renaissance man Thomas Young, for example, deduced that the Stone’s “cartouches” (oval lines surrounding certain words) represented the name “Ptolemy,” the Egyptian pharaoh at the time of the Stone’s inscription.

But it was Jean-Francois Champollion, the “Founding father of Egyptology,” who finally unlocked the Stone’s secrets.

Champollion, born in France in 1790, had an incredible talent for ancient languages from a young age. Particularly useful was his knowledge of Coptic, a “descendant” language of ancient Egyptian. Champollion knew Coptic so well that he translate it “for fun” and even had daydreams in the language.

Champollion never actually saw the Rosetta Stone. He worked instead from copies of the slab’s inscription, laboring indefatigably for years, writing at one point: “I sleep two or three times a week with the Rosetta inscription. So far I’ve only gained headaches and two or three words.”

Portrait of Champollion, Léon Cogniet, 1831. The Louvre/Wikimedia.

But untold hours of labor later, on September 22, 1822, Champollion finally cracked the code, shouting “I’ve got it!” in front of his brother before fainting and spending the next five days in bed. After he recovered, Champollion presented his findings through the “Lettre à M. Dacier” to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in Paris, a renowned French historical society, on September 27. The British museum has claimed this public reading of the letter “marked the birth of Egyptology.”

Before Champollion, scholars believed that hieroglyphics were ideographic, meaning they “represented things or ideas” instead of actual sounds. Champollion made his breakthrough in large part because he came to understand that “hieroglyphs are not strictly ideograms nor solely phonetic signs, they are both... Hieroglyphs depict ideas but they can also be sounds, exactly like our own letters.”

Champollion’s discovery was the “E=Mc2” of Egyptology. His insight unveiled the land of the pharaohs in from its indecipherable obscurity, blazed a trail for future Egyptologists to follow, and fueled the West’s “Egyptomania” during the 19th century and beyond.

Though Egyptology’s founding father died at the young age of 41, France still cherishes his legacy. In 2022, to mark the bicentennial of Champollion’s achievement, France held a countrywide celebration featuring exhibits related to ancient Egypt and Champollion’s work. His hometown, Figeac, launched a “six-month program called ‘Eurêka!’” that included “concerts, movie screenings, theatrical shows, museum exhibits and seminars with leading Egyptologists.”

For all the excitement around the artifact, it contains a fairly prosaic text that has been described as “formal, fulsome, and rather boring.” The inscription commemorates Ptolemy V’s coronation, sings his praises, and gives instructions for how to celebrate the coronation before closing with an injunction to copy and spread the text far and wide throughout Egypt.

Statue of Horus in the Temple of Hatshepsut, Ancient Egypt, Vyacheslav Argenberg. Wikimedia.

It’s a small historical irony that this artifact, which had such tectonic consequences for the study of ancient Egypt, contains a dry, mass-produced announcement. But the story of the Rosetta Stone itself is fascinating. Found by accident and poured over by Europe’s brightest academics—chief among them, Champollion—this slab of stone proved the key that unlocked gripping tales of pharaohs, wars, and myths that still fascinate the world today.