In 1967, the liberal political thinker and future United States Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan was invited by Phi Beta Kappa’s Harvard chapter to deliver a lecture on the divisions within the American left. He was an apt choice. Few alive shared Moynihan’s qualifications: in his four years as Assistant Secretary of Labor under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, he’d helped to define and execute Cold War liberalism’s policies. Soon after leaving politics to become a Harvard professor, Moynihan found himself waging war with the new left’s young activists. One could expect that these experiences would lead the often pedantic New Yorker to condemn the Democrat Party’s youth revolt, but instead, he offered a balanced, illuminating account of post-war liberalism’s inherent problems and offered his own solutions as an alternative to the activism. His dire warnings about the state of liberalism were ignored in his lifetime, which made the emergence of the turbulent culture wars far more likely. But today’s problems are largely the same, and we would do well to remember the late senator’s advice.

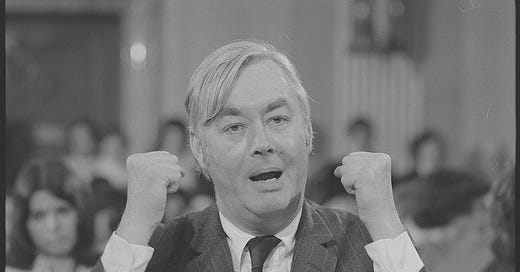

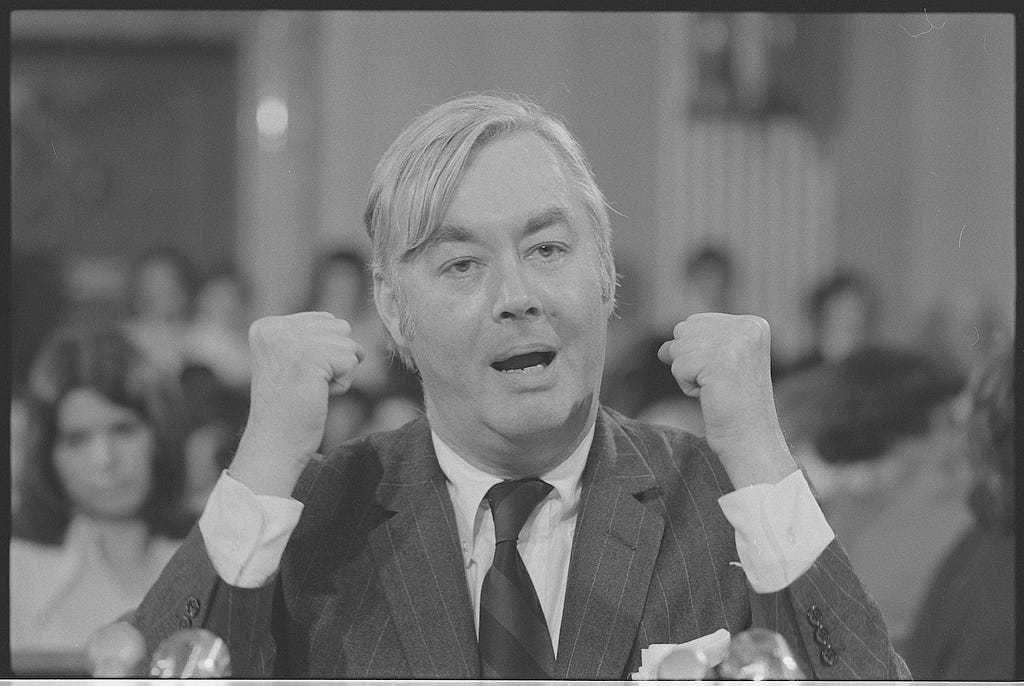

Daniel Patrick Moynihan gestures during a committee hearing in March 1976. Marion S. Trikosko, U.S. News & World, Report Library of Congress.

Moynihan highlighted first the naïve optimism liberalism so often displays. He argued that liberals are too inclined to assume that history consists of human equality and freedom’s inevitable advancement. Such seemingly harmless and comforting confidence is too often combined with an imprudent and dangerous desire to hasten the march of progress. “Liberals have simply got to restrain their enthusiasm for civilizing others,” Moynihan said, “It is their greatest weakness and ultimate disease.” This naivety led to foreign policy disasters, including the doomed-to-fail Vietnam War, which was understandably disconcerting to those asked to risk and give their lives on behalf of a meddlesome fool’s errand.

Building upon his first critique, Moynihan argued that the left’s idealism blinded them to American society’s persistent innate illiberalism, examples of which were easy to find in 1967. After all, the question of civil rights still gripped the country in often violent turmoil. Yet, Moynihan argued, racial animus cannot be removed with a simple handwave and a good high school curriculum, a fact many of the liberal intelligentsia ignored. In short, some ideas are too entrenched for public policy’s blunt instruments.

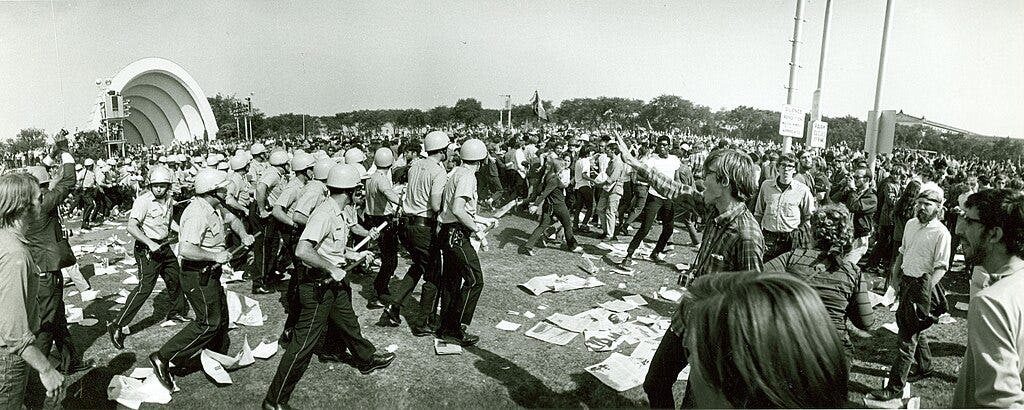

Police clash with Grant Park protestors during the riotous 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Criminal case files, National Archives.

How did liberals become so blinded by their idealism? Moynihan’s seemingly odd assessment was that they had become too reasonable. The intellectuals of his age, he argued, always sought total rationality and thus allowed “the wellsprings of emotion” to dry up. In the end, such liberals could not help but see “the tribal attachments of blood and soil” as somehow unseemly and primitive. Moynihan did not deny the destructive power of such emotional bonds, but he saw them as natural to human nature. Thus we should never ask how to eradicate ethnicity and multiculturalism, but instead, how to live together in a diverse and pluralistic society.

Moynihan offered no easy answers, but he argued that solutions must begin with the liberal recognition of the reality of group cohesion, even for those we find distasteful.

Today, many years later, Moynihan’s speech remains relevant. Nearly all Americans profess to be pluralist liberals, but, in reality, both the left and right struggle to accept those they find unsavory. Just as in the seventies, their instinct is to legislate and reform those with whom they disagree. Moynihan’s lecture reminds us that such policies are doomed to failure: pluralism and tolerance cannot be applied selectively. No amount of bureaucratic interference will force human beings to relinquish their attachment to their faith, tradition, and homeland. Moynihan’s challenge to the right is similar: unifying nationalism can never fully substitute for our ethnic heritages and personal identities.

Ambassador Daniel Patrick Moynihan at the United Nations Security Council in 1976. Bernard Gotfryd, Library of Congress.

Building a pluralist society in which all traditions and ethnicities live together and thrive using Moynihan’s advice is a complicated task. It is possible only if we follow Moynihan’s final suggestion and abandon our utopian visions. Human beings are incapable of conceiving a way of life that offers happiness to all people, in all places, at all times. Our attempts lead to an unhelpful oversimplification of facts at best and often to totalitarian nightmares. Human beings are sad, fallen, creatures who cling to what earthly solace we can find. Any political movement that forgets this eternal fact is doomed to failure.

Jeffery Tyler Syck is an assistant professor of Political Science and American Studies at the University of Pikeville.

I love it. Good piece, I haven't thought about thus particular Moynihan commentary in long time. Perhaps the utopian view that most needs to be addressed, by the right at least, is the idea that the majority of political power shall reside at the federal level - this utopian view was born of the progressive era and locked into place in the FDR/Post WWII era. Perhaps we can turn from this utopian top down society and regain a federalist system of healthy differences and diffuse power.

It's likely our only hope.