Napoleon's Most-Lasting Achievements Weren't On The Battlefield

The real man bears little resemblance to the caricature

Napoleon Bonaparte was born 254 years ago, August 15. One of history’s most most famous Frenchmen, he was born on the Italian island of Corsica, named Napoleone Buonaparte. France annexed the island only a year before Napoleon’s birth, and he spent his early life detesting the French and supporting Corsican independence.

Despite Napoleon’s hatred of France, his father sent him to the French military academy of Brienne, when he was just eight years old. School wasn’t easy for Napoleon. He spoke French with a heavy Corsican accent and was bullied by his colleagues, although not everything was gloomy during this time: at one point, he organized a massive snowball fight at the school, perhaps showing an early inkling for military strategy. He was also a good student and especially loved history, about which he would say: “History I conquered rather than studied.”

After graduating from Brienne, Napoleon moved to the Paris Ecole Militaire academy and eventually became an artillery officer. Unfortunately for the young, ambitious Corsican, the French military at the time was dominated by the aristocracy, and an outsider like him from a minor Italian noble family could only rise so far up the ranks.

Fortunately for the future emperor, something would happen that would shake the foundations of French society and clear his path, not just to the highest rungs of military command, but also to France’s throne—the Revolution.

An Incident during the Massacre. Loyalist Gen. Charles François de Virot de Sombreuil and his daughter leaving the prison. Walter William Ouless. Museums Sheffield/Wikimedia.

The radicals in charge of France’s new revolutionary government killed or drove into exile many of the aristocratic officers serving in the army and navy, creating a vacuum that ambitious men clamored to fill, including one young Corsican artillery officer. At the same time, France needed all the military talent it could muster, as its excess of revolutionary zeal led it into war with all of Europe’s major monarchies.

Napoleon’s astonishing military career began in earnest with his first victory when he was an army captain, taking the port of Toulon from an alliance of British troops and French rebels. As a result of his victory, he was promoted to brigadier general, aged only 24.

He was then given command over a demoralized, undersupplied, and outnumbered French army in Italy that was fighting against the Austrians and their local allies. In this first major campaign, Napoleon led his army into a series of brilliant battles that smashed the Austrian opposition, winning the respect and admiration of both his soldiers and his subordinate commanders—some of whom were older, experienced officers.

Napoleon then led a French army into Egypt in an effort to conquer his way east and undermine the British hold over India. During this mission, his army discovered the Rosetta Stone—a stone slab bearing multiple ancient scripts that allowed the French Scholar, Jean-François Champollion, to eventually translate the hitherto unknown ancient Egyptian alphabet and put the field of Egyptology on the map.

The Battle of the Pyramids. Louis-Francois, Baron Lejeune. Palace of Versailles. Wikimedia.

Though Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt failed—in large part because of the gifted British admiral, Horatio Nelson, who defeated the French navy in the Battle of the Nile—his military exploits won him enough fame and power that he was able to return to France and launch a coup against the corrupt and ineffective government of the time, the Directorate, declaring himself “First Consul” in 1799. Four years later, he would go a step further and declare himself Emperor of the French, later claiming: “I found the crown in the gutter. I picked it up and the people put it on my head.” He was crowned emperor on December 2, 1804, aged just 35.

But Europe’s other crowned heads did not sit idly by. They looked down on Napoleon as a usurper, an upstart, and a product of the French Revolution. If the newly minted emperor wanted to keep his hard-won throne, he would have to fight.

And fight he did. Over the next several years, Napoleon would win smashing victories that military academies still study to this day. One of his most innovative strategies was the adoption of the corps system, by which he split each army into multiple corps, or “mini armies,” each with its own complement of infantry, cavalry, artillery and support troops. This system allowed him to march with his troops widely dispersed, empowering them to move quickly and fall upon the enemy from multiple directions.

Napoleon Bonaparte in the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire in Saint-Cloud. François Bouchot. Palace of Versailles/Wikimedia.

This, along with his ability to find unorthodox yet genius tactical solutions and the admiration of his troops, all combined to make him one of history’s greatest military geniuses. It’s understandable why one of his enemies, the Duke of Wellington, said that Napoleon’s “presence on a battlefield was worth forty thousand men.”

His campaigns were marked by quick marches that sought to engage the enemy as quickly as possible, crushing them in a single battle or two so that France wouldn’t have to fight a prolonged war of attrition.

The Battle of Austerlitz, 2nd December 1805. François Gérard, Palace of Versailles/Wikimedia.

On December 2, 1805, exactly a year after his coronation as emperor, Napoleon won his most famous victory, defeating a coalition of Austrians and Russians in the Battle of Austerlitz. The following year, he defeated a Prussian army in the Battle of Jena, following up that victory with a quick pursuit that denied the Prussians any time to regroup, and occupying their entire country. The next year, in 1807, Napoleon defeated his last remaining enemy on the continent, Russia, in the Battle of Friedland.

Napoleon now dominated all of mainland Europe. France had either annexed or vassalized The Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, and a large part of Germany. The rest of Europe, he had humiliated in battle and forced to make peace.

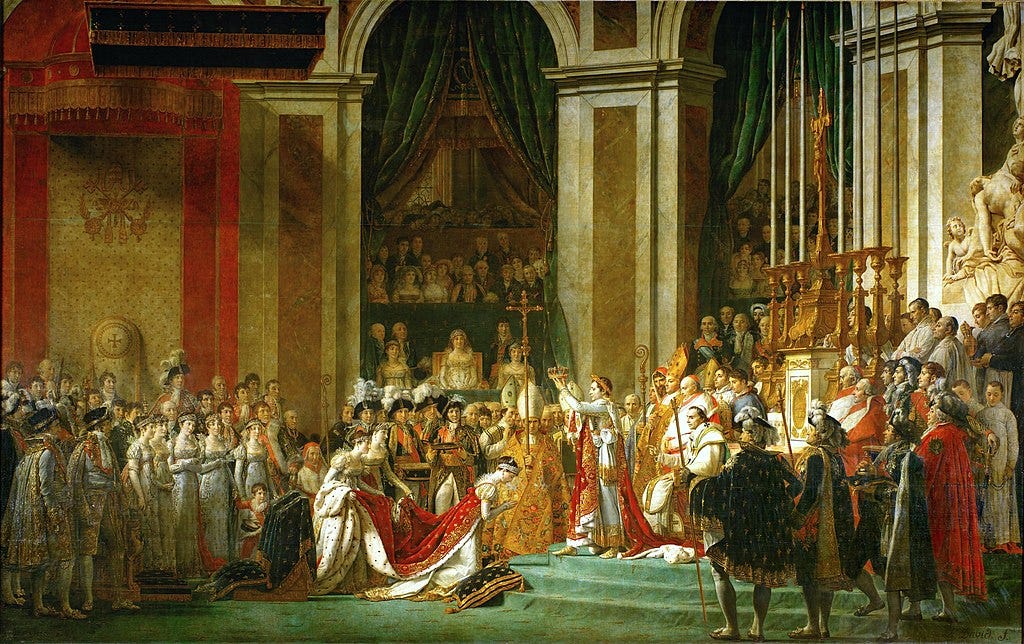

The Coronation of Napoleon, featuring Pope Pius VII. Jacques-Louis David and Georges Rouget. Louvre Museum/Wikimedia.

But there was one country his armies couldn’t reach: Great Britain remained Napoleon’s stalwart foe. Though they didn’t send any armies to face the French, knowing they were no match for Napoleon’s Grande Armée, the British spent freely to encourage other European powers to declare war on France. More importantly, Britain’s Royal Navy blockaded France, hurting its trade and stopping any French naval invasion from reaching England’s shores.

A British admiral at the time expressed Britain’s sense of security by saying: “I do not say the Frenchman [Napoleon] will not come. I only say he will not come by sea.”

Napoleon knew any attempt to cross the channel would be blown apart by Britain’s ships of the line—especially after the British defeated a French-Spanish fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar, which was conducted, again, by the British admiral Horatio Nelson (Nelson perished at Trafalgar, dying at the moment of his greatest triumph but assuring British naval dominance for a century). Instead, Napoleon imposed the Continental System on France and its allies, which was a Continent-wide embargo on British goods meant to weaken the island nation economically and force it to negotiate.

The Battle of Trafalgar. J. M. W. Turner. National Maritime Museum/Wikimedia.

This system, however, backfired. Smuggling was widespread in contravention of the French emperor’s edicts, and European powers hated suffering economic pain for what they perceived as French interests. The Continental System didn’t hurt Britain economically in the long term—the British, with a free run of the world’s oceans, simply shifted their trading to other parts of the globe.

It was in part due to his desire to enforce the Continental System that Napoleon made one of the most disastrous choices of his career: invading his one-time ally, Spain. The war in Spain did not conform to the Napoleonic way of quick campaigning crowned by a decisive, face-to-face battle. Though this conflict, which came to be known as the Peninsular War, involved pitched battles, it was also marked by a brutal six-year-long guerilla campaign against an enemy that hid in every bush. (Coincidentally, the Peninsular War is the reason why we have the term “guerrilla warfare”.)

Even more disastrously, the Continental System—among other factors—also pushed Napoleon into the biggest mistake of his life: invading Russia.

Napoleon leaves the Kremlin. Maurice Orange/Wikimedia.

Contrary to some beliefs in popular culture, Napoleon invaded Russia in the heat of June, not in wintertime, and he lost more troops during the march towards Moscow than during his wintery retreat. The vast distances of Russia, widespread disease, supply problems, raids by Cossack cavalry, and partisan warfare all took their toll on his army. Napoleon had gone into Russia with more than 600,000 troops gathered from all over Europe (only about half of his troops were French) but he returned with only a handful.

Yet Napoleon still did not surrender. He raised new armies, and, astonishingly, managed to win several more victories over the armies of the anti-French coalition.

But the pendulum had finally swung against him. He could not follow up his victories as he did in times past; his armies were made up of new, inexperienced conscripts, he lost his entire cavalry force in Russia’s endless plains, and now all of Europe was united against him.

Europe’s united forces eventually pushed him back within France’s borders, and, although he incredibly managed to win another series of battles outside the gates of Paris—as part of his Six Days’ Campaign—he was ultimately defeated in 1814 and forced to abdicate and retire in exile to the island of Elba in the Mediterranean.

Napoleon’s Return from Elba. Charles de Steuben. Private collection/Wikimedia.

Napoleon returned to France the next year, reassuming his place as emperor and winning his last victory at the Battle of Ligny against the Prussians, but he lost the Battle of Waterloo against a combined allied army and was forced to abdicate again. He was exiled by the British to the desolate island of St. Helena in the Atlantic, where he would spend the last six years of his life closely guarded by the English, who made sure their archenemy would never again have the chance to escape.

Though Napoleon’s military exploits are what usually come to mind when we think of the French emperor, his non-military reforms also had a huge effect on the world. He drafted a law code for France known as the Napoleonic Code, which not only codified France’s confused jumble of laws, but also guaranteed property rights and “equality before the law, freedom of religion and the abolition of feudalism”.

The Code’s impact stretched far beyond France—these ideals would ferment in France’s formerly-conquered territories long after the defeat at Waterloo. It became the inspiration for legal systems from Latin America to Louisiana. Not for nothing did Napoleon say: “My real glory is not the forty battles I won . . . What nothing will destroy, what will live forever, is my Civil Code.” The global reach of the Napoleonic Code is reflected in the fact his marble image hangs in the U.S. Congress, alongside twenty-two other “historical figures noted for their work in establishing the principles that underlie American law.”

Napoleon also improved Paris itself, building the monumental and world-famous Arc de Triomphe, playing a role in making the Louvre what it is today (indeed, the museum was briefly named the “Napoleon Museum”), and constructing the Rue de Rivoli, “one of the most famous streets in Paris.” Besides these more famous examples, the emperor also undertook a broader, ambitious program of public works in the capital, playing a role in transforming it into the City of Lights we know today.

Statue of Napoleon I in Cherbourg-Octeville. Eric Pouhier/Wikimedia.

Napoleon also, as the British historian Andrew Roberts points out, “created the educational system based on lycées and Grandes écoles and the Sorbonne, which put France at the forefront of European educational achievement. He consolidated the administrative system based on departments and prefects. He initiated the Council of State, which still vets the laws of France, and the Court of Audit, which oversees its public accounts,” and “organized the Banque de France and the Légion d’Honneur, which thrive today.”

Napoleon is often caricatured as a warmongering proto-Hitler, but the image is false. He was one of the greatest military leaders of all time–a complex, fascinating figure, and a visionary whose reforms have shaped not only France, but the world.