Nine Must-Reads For 2024

Your year's guide, from the world's smartest scholars

There are eight books on my nightstand this morning. They range from a biography of Shane MacGowan to a tome I’m halfway through on how the Holy Roman Empire was organized. Authors include Aldous Huxley and Ernest Hemingway. My wife assures me the latter’s self-infatuated tale of a drunk and depressed World War I veteran in Paris is one of life’s greatest novels. I’m unconvinced so far, but I’ll keep reading when I can find the time. It’s a story of conversion, after all.

Downstairs there are three cookbooks I’ve promised to put away once I’ve finished. Progress is slow. There’s a book about being a better husband and dad tucked away somewhere too, I know.

It can be hard to find time to read a good book in a world overrun by Instagram, Twitter, work and the news cycle. Often, we’ll find ourselves reading thousands of pages a week without ever opening the real thing. This is terrible. It cheapens us, and makes us dumber. As with exercise, we know we’ll never simply find the time–we have to make it. This takes setting goals, and cultivating the discipline to meet them, but it is essential to keeping us human.

Our scholars and faculty have compiled a few of their favorite reads below to make it just a little easier to find that new great book you’ve been looking for, or aid in remembering that classic you’d always hoped to crack.

We hope you enjoy them. Merry Christmas, and happy New Year.

Sincerely,

Chris

—-

Executive Editor

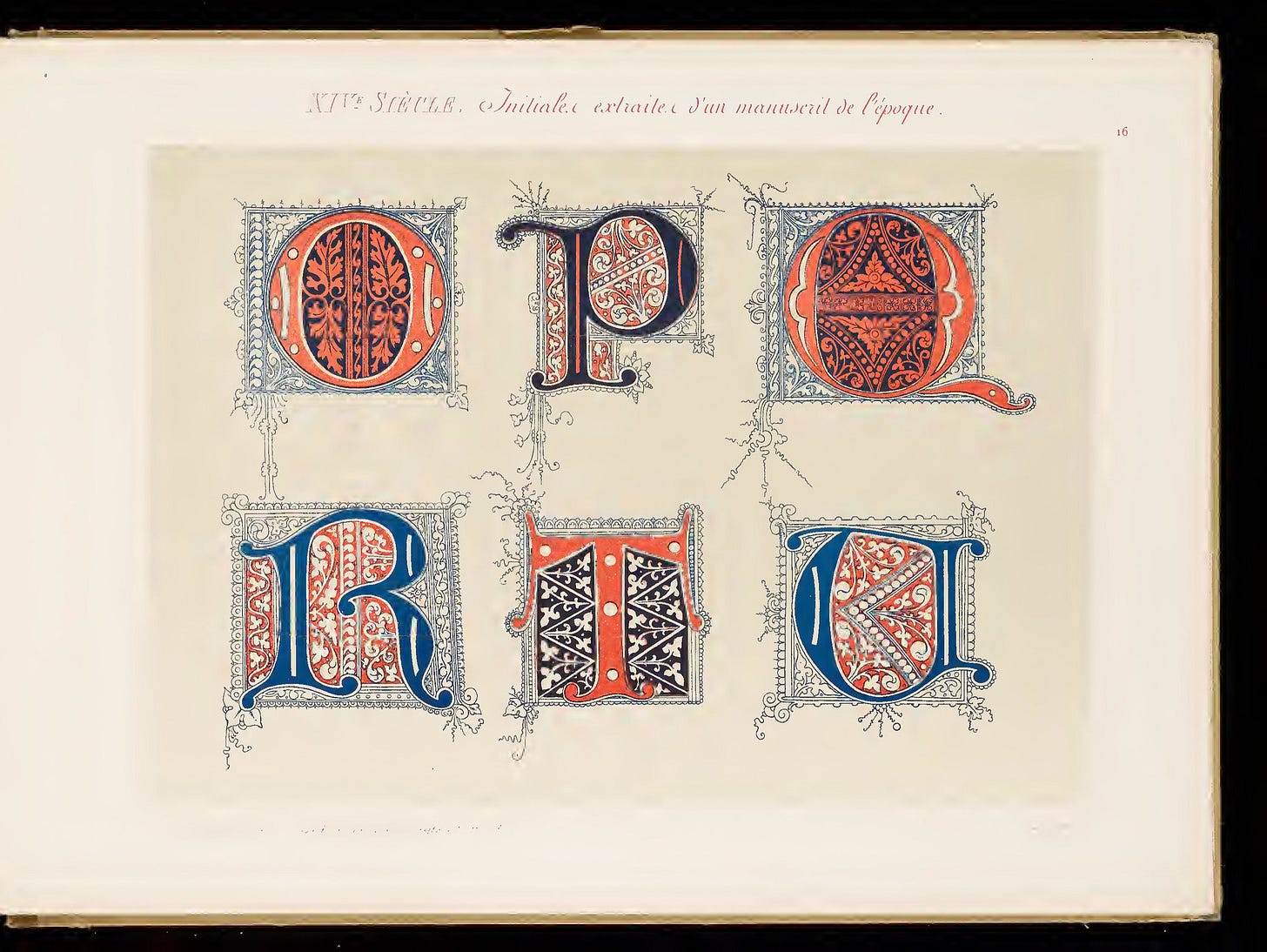

Trésor Calligraphique, Louis Seghers, 1878. TheCMN, Flickr.

Dr. Melvin Schut is the director of Common Sense Society–The Netherlands. He is a board member of the Amstel Institute for the Liberal Arts and Sciences, and a political science faculty member at Amsterdam University College. His recommendations are below:

The Soul of Politics – Harry V. Jaffa and the Fight for America, by Glenn Ellmers

In recent years Glenn Ellmers put his finger on the shortcomings of “conservatism” and drew the ire of Frank Fukuyama for questioning the “Americanness” of American citizens who reject the principles of the Founding. In 2021 he published The Soul of Politics – Harry V. Jaffa and the Fight for America, a wonderful tour de force explaining the mind of Harry Jaffa. With it, Ellmers convincingly established Jaffa as a profound, underrated and prescient thinker of enduring relevance, who had in important ways emancipated himself from his teacher, Leo Strauss.

The Narrow Passage – Plato, Foucault and the Possibility of Political Philosophy, by Glenn Ellmers

Building on that, this year Ellmers presented The Narrow Passage – Plato, Foucault, and the Possibility of Political Philosophy, a small book applying Jaffa’s key insight that progressivism can be defeated only if it is understood to have been defeated intellectually. “The United States,” Ellmers writes, “seems to be ruled today as a post-constitutional regime, governed by a secular theology cobbled together from various modern European philosophers (predominantly, though not exclusively, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, and Heidegger).”

In his new book, Ellmers argues that these ideas can and should be defeated by a disciplined return to “common sense.” Still, if this is possible, perhaps the ideas that Ellmers warns against are not as philosophically powerful as his book suggests. Perhaps the real question about their enormous influence concerns their rhetorical appeal, particularly to today’s academic class. Why do people profess the things that they do? Why are they seduced, particularly when they should know better? Bad boys tend to get the girl because they’re dark and exciting, not because they have the better argument. Good guys would be wise to learn from that.

Trésor Calligraphique, Louis Seghers, 1878. TheCMN, Flickr.

Piotr Trabinski is a senior fellow at Common Sense Society and a former International Monetary Fund executive director, where he worked on fiscal and monetary policies, financial sector supervision, central bank digital currencies, fintech regulation, anti-money laundering, and combating terrorism financing. His recommendations are below:

Hamilton, by Ron Chernow

Ron Chernow's Hamilton was among my favorite books to read in 2023. It is a captivating biography that explores the life of Alexander Hamilton, one of America's Founding Fathers. This book provides a vivid portrait of Hamilton's complex character, detailing his contributions to shaping the U.S. financial system, economic and foreign policies. Chernow offers not only historical insights, but a compelling narrative, crafting an engaging read for those interested in history, politics, economics and foreign policy, as well as the human stories behind the birth of a nation. I chose it specifically to better understand the U.S. economic fundamentals, but found much more than I expected.

The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci, by Jonathan Spence

Jonathan Spence's The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci is a thought-provoking exploration of cultural exchange and memory in 16th-century China. Focused on the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci, Spence presents the challenges of cross-cultural communication through the lens of memory techniques employed by Ricci, but developed centuries before by ancient Greek philosopher Simonides of Ceos. The book combines history, philosophy, and cultural studies, making it a memorable experience for anyone interested in understanding the complexities of East-West interactions, and the power of memory and imagination.

Trésor Calligraphique, Louis Seghers, 1878. TheCMN, Flickr.

Dr. Joshua Mitchell is a senior fellow at Common Sense Society and a professor of political theory at Georgetown University. His books include Not By Reason Alone, The Fragility of Freedom, Plato's Fable, Tocqueville In Arabia, and American Awakening. He is currently working on The Gentle Seduction Of Tyranny. His recommendations are below:

Christmas is a season in which we remember and celebrate the divine gift, the Incarnation. Our pale mortal imitation of that miracle is gift-giving. No book written by mortal hand is divine, but some books are, shall we say, timeless rather than merely contemporary. These two books are timeless.

Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville, J. P. Mayer ed.

Here is perhaps the greatest book ever written about America. Read it not only to understand early America, but to diagnose what has gone wrong in our beleaguered country, and how we can, as citizens, fix it. The great danger that awaits us, Tocqueville wrote, is the emergence of a citizenry that is isolated and alone, along with an increasingly powerful state that promises to take care of us but cannot. The remedy is painful but effective: turn to your neighbors and local community. There are treasures there, through which we can rebuild America.

The Major Political Writings, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Scott trans.

This book contains three important long essays, all written at the beginning of “modernity.” What is Rousseau doing in these works? He is trying to understand how to think about who we are, though in a new way.

In the first essay, he gives us the distinction between ancient virtue and modern self-interest—a distinction that has been the basis of almost every anti-modern work written after him. In the second essay, he gives us the distinction between nature and society—a distinction that has allowed generations to develop theories of the so-called natural goodness of man. I do not recommend Rousseau because I think he can be a guide for us today; I recommend him, because he inaugurates a strand of thought that lives in the hearts and minds of millions of people around the globe, even if they have never read him.

Trésor Calligraphique, Louis Seghers, 1878. TheCMN, Flickr.

Catesby Leigh is a senior fellow at Common Sense Society, and a co-founder of the National Civic Art Society. You can find his work in City Journal, The Wall Street Journal, First Things, The American Conservative, and the Claremont Review of Books. His recommendations are below:

The Golden City, by Henry Hope Reed

One of my favorite books of this, or any, year is my mentor Henry Hope Reed's The Golden City. First published in 1959, Henry's book was the first major postwar denunciation of modernist architecture to appear in this country, picking up where the brilliant British writer Geoffrey Scott left off with The Architecture of Humanism, written on the eve of World War I. Henry, who lived for nearly a century and died in 2013, was acutely aware that modernism embodied the narrowing of our civilization's imaginative horizons, and he was very attentive to intellectual developments in this country that facilitated its rise.

It's hard to believe, but true, that when he wrote his broadside, classical architecture had been relegated to an even more marginal status than is the case now. The Monacelli Press and the Institute of Classical Architecture chose wisely in re-printing the first edition of The Golden City rather than the paperback second edition of 1971. The cultural ambiance of the 1950s--the decade during which the modernist predominance in the United States was clinched--permeates Henry's erudite argument for the great tradition. My good friend Alvin Holm, a distinguished Philadelphia architect, and yours truly had the privilege of writing introductory essays to the new edition of this truly extraordinary book, which appeared in 2020.

History of Western Architecture, by David Watkins

Another favorite to which I repeatedly return is the late Cambridge scholar David Watkin's A History of Western Architecture. This 700-page tome, first published in 1986, starts with Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia and continues down to the present time. The last (sixth) edition published in his lifetime appeared in 2015, but I confess to being content to own the fourth edition from 2005.

Watkin's main contribution was his brilliant account of architecture's formal development during classical antiquity, the early and late medieval periods, the Renaissance and so on. His account of early modernist trends in different countries is enthralling. Watkin's understated ambivalence toward the modernist hegemony that took root in Europe between the World Wars was complemented by a deep conviction in classicism's boundless capacity for adaptation to changing historical circumstances. It is hardly surprising that he should have been a member of the former Prince of Wales's inner circle.

Trésor Calligraphique, Louis Seghers, 1878. TheCMN, Flickr.

David Talbot is the executive vice president and chief development officer for Common Sense Society. His recommendation is below:

Cultural Amnesia; Necessary Memories from History and the Arts, by Clive James.

Greatness is not everything, argues James, the late and prolific author, journalist, TV presenter, and Australian expat in London. "A civilization is irrigated and sustained by its common interchange of ordinary intelligence."

The chapters are short essays about individuals, arranged alphabetically. Some of the characters I had some familiarity with, such as Miles Davis, Czeslaw Milosz, Octavio Paz, and Charlie Chaplin. Others I was grateful to be introduced to: Stefan Zweig, Lewis Namier, Eugenio Montale, and Isoroku Yamamoto, to name a few. In all cases, James's sweeping theme and intelligent commentary filled in some significant gaps in my mental map of 20th century history. One salient example was the vibrant intellectual cafe scene in Vienna before the Second World War, where many of the leading figures were Jewish.

One trait of a good book for me is that spurs me to investigate other authors and get their books. I must have bought two dozen books as a result of reading this one. James was a great stylist and could turn memorable lines, and he offers up some gems for logophiles, such as "gazofilacio," an untranslatable Italian word for the mental bank account you acquire by memorizing poetry, which James knew in abundance.

Thanks for much for the nice recommendation of both of my books! Happy New Year.