Poetic Justice Beats Woke Social Justice

America’s high-school poetry competition has taken the road less traveled by

Against the odds, America’s high-school poetry competition has taken the road less traveled by.

I attended the Poetry Out Loud national championship this month to see if the popular program has given into the woke madness sweeping the rest of education. Surprisingly, it has not, giving me hope that at least some of our country’s students are still studying the words and wisdom of poets past.

Poetry Out Loud is the brainchild of Dana Gioia, a poet who served as chairman of the National Endowment of the Arts under President George W. Bush, and a mentor of mine. Launched during his chairmanship in 2005, the program asks participating high-school students—more than 4.1 million so far—to memorize and recite three poems. State championships lead to nationals, held this year at George Washington University. If the joy of learning poetry isn’t payment enough, the winner also gets a cool $20,000.

As a poetry buff, I’ve always rued that I missed out on Poetry Out Loud, having graduated high school before it launched. I set out to hear for myself which poems today’s students learn by heart, and equally important, which poems the judges reward. It wasn’t a strong start. The judges were predominantly progressive literary types who have little taste for tried and true. Nor was it encouraging when the emcee praised the guest DJ for his diversity and intersectionality. I braced myself for a strong dose of social justice hectoring in the poems I was about to hear.

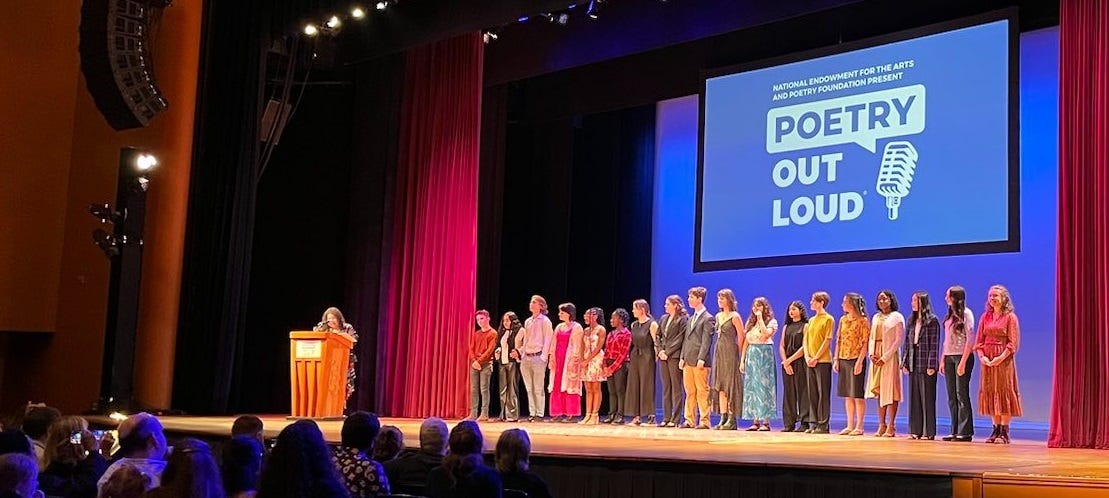

The Poetry Out Loud finals, May 2023. Photo by Davey Talbot.

But the students surprised me. The first contestant of the day offered up “On the Death of Anne Brontë,” a fine lyric elegy. I then enjoyed impressive recitations of Keats, Wordsworth, Donne, Dickinson, Auden, Herbert, Hopkins, and many others—quite a respectable range of dead poets. The students themselves came from diverse backgrounds, and their interests in poetic style and range were even more varied. One young man paired “The Charge of the Light Brigade” with “Frederick Douglass” by Robert Hayden.

Was there any woke verse? Some. Yet by my count, for every in-your-face political diatribe, there were at least a dozen solid poems appealing to the better angels of our nature. That included many contemporary poems, proving that poetry can be relevant and edifying when it doesn’t sink to propaganda. Of the nine poems recited by the three national finalists, only one delivered a social justice sermon, which at least had the virtue of being clever: “You are not presumed to be innocent if the police/have reason to suspect you are carrying a concealed wallet.”

Poetry, A-Z. Photo by Brewbooks/Flickr.

The whole experience defied my expectations. Part of the reason Poetry Out Loud hasn’t devolved into leftist political theater is its strong requirements. Students must choose their poems from the official Poetry Out Loud Anthology containing more than 1,000 entries from across literary history. Many of the newest are blatantly political (see the one, which I heard at the finals, that includes a long list of first names starting with Breonna and ending with Tamir—a reference to people who’ve died at the hands of police). But most of the poems are older and have stood the test of time.

It also helps that at least one of each student’s three poems must have been written before the 20th century. Yet that still leaves them with the freedom to choose two more radicalized options. Having browsed the anthology, which is searchable by themes including “Celebrating LGBTQ Pride,” “Social Justice and Equality,” and “Poems of Protest, Resistance, and Empowerment,” I expected more politicized poems than there actually were. Clearly, some poets exert a stronger pull on the heart. So do some topics. Throughout the finals, the ageless themes of death and love ruled the day.

A young Benjamin Franklin reads by candlelight, from his autobiography, 1849. Public Domain.

I hope Poetry Out Loud maintains its commitment to excellence. The requirement for one pre-20th century poem could easily be discarded. The scoring criteria, currently weighted for accuracy, could be adjusted. The anthology could be culled of beloved and well-known poems. The National Endowment for the Arts and the Poetry Foundation, which jointly organize Poetry Out Loud in cooperation with state arts agencies, certainly have different priorities than Gioia had when he launched the program.

Perhaps they haven’t ruined this competition because they know it will fail if politicized. As I saw firsthand, most students don’t sign up because they see it as a platform for activism. They would rather memorize and recite good poems. Poetry Out Loud still serves our country well by promoting, as Robert Frost described poetry, “a way of remembering what it would impoverish us to forget.” When the national finals roll around next year, I’ll take my son.