The Battle of Lepanto: The Little-Known Naval Battle That Saved The West

How a Christian coalition put aside its differences to defeat a common foe

Midway, Salamis, and Trafalgar: these naval battles changed world history and are widely known, featuring in our movies, novels, and school textbooks. But odds are you haven’t heard of a naval battle fought on October 7, 452 years ago today, that stopped a rapacious and aggressive empire in its tracks: the Battle of Lepanto.

The Battle of Lepanto was the last great battle between galleys—maneuverable, primarily oar-powered and cannon-bearing ships—and it saw an alliance of Christian powers uniting to stop the Ottoman Empire from running rampant across the Mediterranean.

The Fall of Constantinople, from Hutchinson's History of the Nations, illustrated by Ambrose Dudley, 1915. The Bridgeman Art Library/Wikimedia Commons.

The Ottoman Turks had been mostly kept out of Europe’s gates by the Eastern Roman (or Byzantine) Empire until they captured and viciously sacked Constantinople, the Byzantine capital, in 1453, killing or enslaving tens of thousands of civilians in the process.

With Europe’s shield now fallen, the Ottomans continued conquering southeastern Europe’s many small nations. Despite heroic resistance—gifted military leaders like Albanian ruler Skanderbeg, or Stephen, the Great of Moldova repeatedly defeated much larger Ottoman armies—the Turkish tide proved unstoppable; the Ottomans’ massive manpower pool allowed them to spend their soldiers’ lives like coins.

Constantinople’s new masters were brutal rulers. The Ottoman Turks treated Christian subjects as second-class citizens, kept them isolated from the West’s important cultural and scientific developments, and imposed a cruel slavery system known as “devshirme,” or “blood tax.” This “tax” involved taking children away from their parents, enslaving them, forcibly converting them to Islam, and then either making them government ministers or turning them into elite “Janissary” troops. The Janissaries would then go back to Europe to fight in more wars and kill or enslave more of their own kinsmen in their new lords’ service.

Nor was Western Europe free of Ottoman depredations. By the late 16th century, the Western Europeans had been fighting a decades-long battle with the Ottomans for control of the Mediterranean. Corsairs from the Ottoman Empire, in particular from the Ottoman-ruled Barbary Coast routinely enslaved Europeans.

As one scholar put it:

Enslavement was a very real possibility for anyone who traveled in the Mediterranean, or who lived along the shores in places like Italy, France, Spain and Portugal, and even as far north as England and Iceland. . . . The impact of these attacks [was] devastating—France, England, and Spain each lost thousands of ships, and long stretches of the Spanish and Italian coasts were almost completely abandoned by their inhabitants.

Europe scored some victories, most notably in the Great Siege of Malta, in which a handful of knights from the Hospitaller crusading order held off tens of thousands of Ottoman troops and forced them into a humiliating retreat from the strategically important island of Malta. But this triumph, great though it was, was still just a defensive victory. The Christians had never achieved a major success while taking the fight to the Ottomans, and despite fighting a common enemy, were riven by factionalism, and just as likely to declare war upon one another as upon their mutually hated foe. It would take a severe hammer blow to force them to band together.

That blow came in 1570 when the Turks invaded Cyprus, at the time an important Venetian-held possession in the eastern Mediterranean. The Ottomans captured the city of Nicosia, murdering 20,000 of its civilians in the process, before laying siege to Famagusta, a Venetian fortress-city on the island’s eastern end.

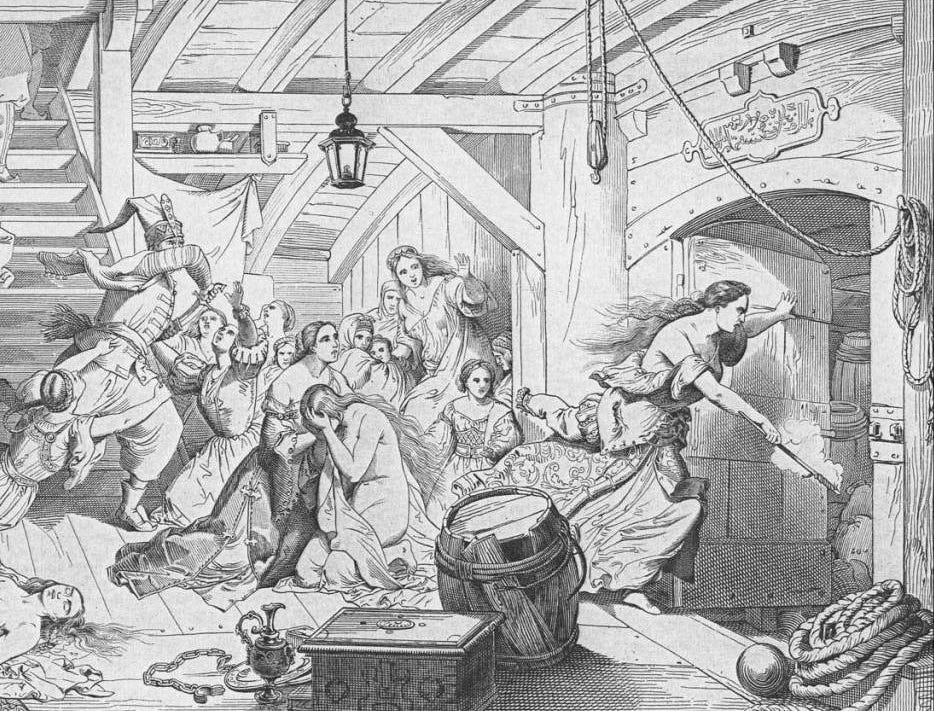

Belisandra Maraviglia blows up a ship carrying herself and other young female prisoners away after the Turkish conquest of Nicosia. Giuseppe Lorenzo Gatteri. Wikimedia.

The Ottoman attack on Cyprus was a wakeup call for the Christians to unify. Pope Pius V, the alliance’s mastermind, built a coalition of the Papal States, Spain, Venice, and several other Christian Mediterranean powers to finally take the war to the Ottomans. Don Juan of Austria, a talented military leader and the illegitimate son of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, took command of a naval expedition to help the beleaguered Venetians.

But divisions remained. As the historian Roger Crowley argues in Empires of the Sea: “Beneath the surface, this magnificent pan-Christian operation was a brawling, bad-tempered, quarrelsome assortment of conflicting egos and objectives;” fights broke out between soldiers and bad blood over past wrongs surfaced. At one point, the alliance deteriorated to such a degree that the Venetian and Spanish contingents were on the cusp of fighting each other instead of the Ottomans.

Even as Don Juan struggled to maintain the tenuous alliance, Famagusta’s Venetian protectors fought for their lives heroically; their defense cost the Ottomans almost a year and heavy losses to force the garrison’s surrender.

Pope Pius V and John of Austria, Gian Paolo Cavagna, Cathedral of Sainte-Marie de l'Assomption de Bastia/Wikimedia.

The brave defenders surrendered after recognizing they could no longer withstand the overwhelming Ottoman assault and were promised safe conduct. But no sooner did the Venetians surrender than the Ottoman commander broke his word, killing his prisoners and torturing their commander, Marcantonio Bragadin, to death.

Perhaps the Ottomans hoped their cruelty would demoralize the Christian fleet sailing towards them, but if so, their plan backfired. As Crowley shows, when news of the Ottoman atrocity reached the Christians, “[It] had a sudden and electrifying effect on the fleet. It focused the Venetian desire for vengeance and instantly soothed divisions.”

Though the fleet was too late to save Cyprus, they still wanted to exact revenge and inflict some damage on the Turks. Their chance finally arrived when they found the Ottoman fleet in the port of Lepanto in the Gulf of Corinth. The Ottoman commander, Ali Pasha, could have remained in port defended by his heavy land-based guns, but he chose to engage, and so did Don Juan, who told his men: “Gentlemen, this is not the time to discuss but to fight.”

The Battle of Lepanto, unknown, 19th century. National Maritime Museum of London. Wikimedia.

Both sides had more than two hundred ships, though the Ottomans had a numbers advantage. But the Europeans had an important trump card—six Venetian galleasses.

If the galley was a cannon platform, then the galleass was a floating fortress, bearing tens of cannons and strengthened sides. Before the Turks could even reach the main Christian battle line, they had to pass through these Venetian juggernauts, which pulverized them and blunted the impetus of their attack.

The galleasses were not the Europeans’ only advantage. The Christians also possessed more and better arquebuses (a primitive type of musket) that softened the Ottoman forces before they could attempt boarding actions. The fighting was desperate—an arrow hit Venetian admiral Agostino Barbarigo, commander of the allied left wing, in the eye, yet he continued to fight relentlessly, only dying of his wounds days later.

The Battle of Lepanto, Cornelis de Wael, between 1613 and 1667, Bonhams, London/Wikimedia.

The decisive battle was fought in the center, where the Christian and Ottoman flagships, bearing their respective fleet commanders, engaged in a close-quarters boarding battle. Ali Pasha, who personally fought in the melee, was killed, and when knowledge of his death became widespread, it broke the morale of the Turkish ships in the center.

Only on the right wing did the Ottomans begin to overwhelm the Christian line, but the coalition forces managed to hold on long enough for reinforcements to come from elsewhere in the battle line and turn the tide.

The result was an utter Ottoman rout. The Christians inflicted more than 25,000 Ottoman casualties, destroyed over sixty ships, and captured almost two hundred of them—from which they liberated roughly 12,000 Christian rowing slaves.

The Victory, Jan Peeters the Elder, 1675, St Paul's Church. Photgraph by Elias, Jean-Luc. Wikimedia.

It was a crushing victory. Some historians have downplayed the Christian triumph, pointing to the fact that the Holy League disintegrated shortly afterwards and never recovered Cyprus, and that the Ottomans rebuilt their fleet after the battle. The Ottoman grand vizier boasted to a Venetian diplomat that: “In wrestling Cyprus from you, we deprived you of an arm; in defeating our fleet, you have only shaved our beard. An arm when cut off cannot grow again; but a shorn beard will grow all the better for the razor.”

But if the Ottoman “beard” grew back, it did so in patches. Crowley quotes a contemporary who saw the rebuilt Ottoman navy, describing it as:

made up of new vessels, built of green timber, rowed by crews which never held an oar, provided with artillery which had been cast in haste, several pieces being compounded of acidic and rotten material, with apprentice guides and mariners, and armed with men still stunned by the last battle.”

It's no surprise this lackluster fleet saw little use. As Crowley points out, “there was a growing distaste for maritime ventures; the Ottoman fleet lay rotting in the still waters of the Horn,” and “The events of 1565–1571 fixed the frontiers of the modern Mediterranean world.” Never again would the Ottomans threaten Western Europe’s coasts to the same extent as they had before Lepanto’s carnage—especially as Western Europe’s shipbuilding technology overtook the Turks’ by leaps and bounds in the coming decades. (More than thirty years after Lepanto, a small force of Spanish galleons defeated a squadron of Ottoman galleys many times its number.)

But Lepanto’s material benefits were secondary to its psychological triumphs. Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote, fought in the battle and called it the “most noble and memorable event that past centuries have seen or future generations can ever hope to witness.”

The victory shattered the myth of Turkish invincibility and gave the West a much-needed morale boost following a string of humiliations. Christians celebrated their victory with paintings and other works of art made by some of Europe’s finest Renaissance masters. Nor did the commemorations stop in the 16th century—hundreds of years later, famed British author G.K. Chesterton would write a poem celebrating the battle and honoring Don Juan.

Allegory of the Battle of Lepanto, Paolo Veronese, 1571. Gallerie dell'Accademia/Wikimedia.

Lepanto was a turning point, regardless of what revisionist historians might say. It halted the Ottoman rampage across the western Mediterranean and bloodied their noses badly enough that they never fully recovered psychologically.

The struggle between Christians and the Turks continued for centuries, but the sailors at Lepanto laid a crucial building block upon which future warriors built.

If you’re interested in contributing to the Common Sense Society Substack, email your pitch to Bedford@commonsensesociety.org.

Great history, but I think “Christian factionalism” doesn’t accurately render a very important aspect of the narrative: Protestant Europe was actively undermining Catholic Holy League, while reformers like Martin Luther praised the Turks as being that “necessary” flog to punish Catholic Europe for its sins.