The Battle To Make Public Architecture Beautiful Isn't Over—It's Just Beginning

Congress has lifted the banner

Republicans in both the House and Senate have found a new battlefield: making American public architecture beautiful again. Beauty was once a central component of government architectural policy, but this field had long been abandoned by Washington politicians. But President Donald Trump’s late-term executive order, “Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture,” resurrected the debate by mandating a preference for classical or vernacular styles when designing new federal buildings. President Joe Biden promptly canceled the order and even took the unprecedented step of forcefully removing its advocates, such as Justin Shubow, from the United States Commission of Fine Arts before the end of their terms. But this fight has reemerged in Congress, signaling the issue’s longevity. The desire for beautiful public buildings is no simple flash in the pan—but the beginning of something bigger.

Republican willingness to advocate for federally mandated classical architecture in D.C. represents a welcome change in the American conservative mindset. Ten years ago, if there was any discussion on federal architecture, most Republicans would have likely only cared about limiting costs or abolishing the proposed building’s government department. Today’s conservatism is embracing tradition, beauty and moral objectivity—three principles that are vital not only to a well-ordered philosophy, but to a well-functioning society.

United States Capitol, Tortola scheme, William Thornton, 1793. Library of Congress.

This proposal, to have classical architecture as the standard or preferred federal architecture, is appealing because it directly aligns with American tradition and history. A quick look through that history yields a continuous and deep connection between our federal government and classical architecture.

When the first Congress decided to build a new capital in 1790, they had to choose the city’s overall architectural style before they could choose plans and begin construction. For Thomas Jefferson, there was no question. In a letter to the city’s designer Pierre L'Enfant, he wrote: “Whenever it is proposed to prepare plans for the Capitol, I should prefer the adoption of some one of the models of antiquity which have had the approbation of thousands of years.”

This preference for classical architecture rested on its connection to antiquity, in particular Greece and Rome. Our founding generation was directly inspired by Greek and Roman philosophy, history, and governance. From our Senate, which takes its name from the Roman Senate, to the representative democracy of our House of Representatives, which has its origins in Greek democracy, many of the Constitution’s elements can be traced to classical civilization. It made sense to our Founders that the structures housing such institutions should likewise be in this style.

United States Capitol, low dome, graphite and watercolor, William Thornton, 1793. Library of Congress.

The United States Capitol is the most well-known example. Designed by William Thornton and completed in 1800, the Capitol was directly inspired by ancient Roman architecture such as the Pantheon and represents American Classicism at its finest. The generations following the Founders continued this architectural tradition. When the Capitol was expanded in the 1850s, both the newer wings and dome were designed in the same style as the original building. From the Library of Congress’s late 19th century Beaux-Arts classicism, to the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials of the 1920s and 30s, federal architecture was always built in the classical style. It was only in the post-World War II period that classical style was replaced with Modernism, giving birth to universally hated federal buildings such as the J. Edgar Hoover Building or the Department of Health and Human Services. Both are built in the aptly named Brutalist style, which recent Republican orders and legislation have explicitly condemned.

Embracing classical architectural design and abandoning modern styles will also offer American cities practical benefits. Urban planners and architects demolished vast portions of our cities in the 20th century, which once rivaled Europe’s in terms of beauty, largely transforming them into parking lots and office buildings. Jane Jacobs, in her monumental work The Life and Death of Great American Cities, lamented that under these planners cities were becoming “monotonous unnourishing gruel.” In most, the only spaces people visit for reasons other than work are the few remaining historic streets or beautiful public monuments. A place’s beauty is a significant factor people consider when deciding to visit or live on a specific street, in a certain neighborhood, or near an attractive square or plaza. Federal buildings, often built in important and central locations, can help foster and create beautiful places, revitalizing our downtown cities and towns.

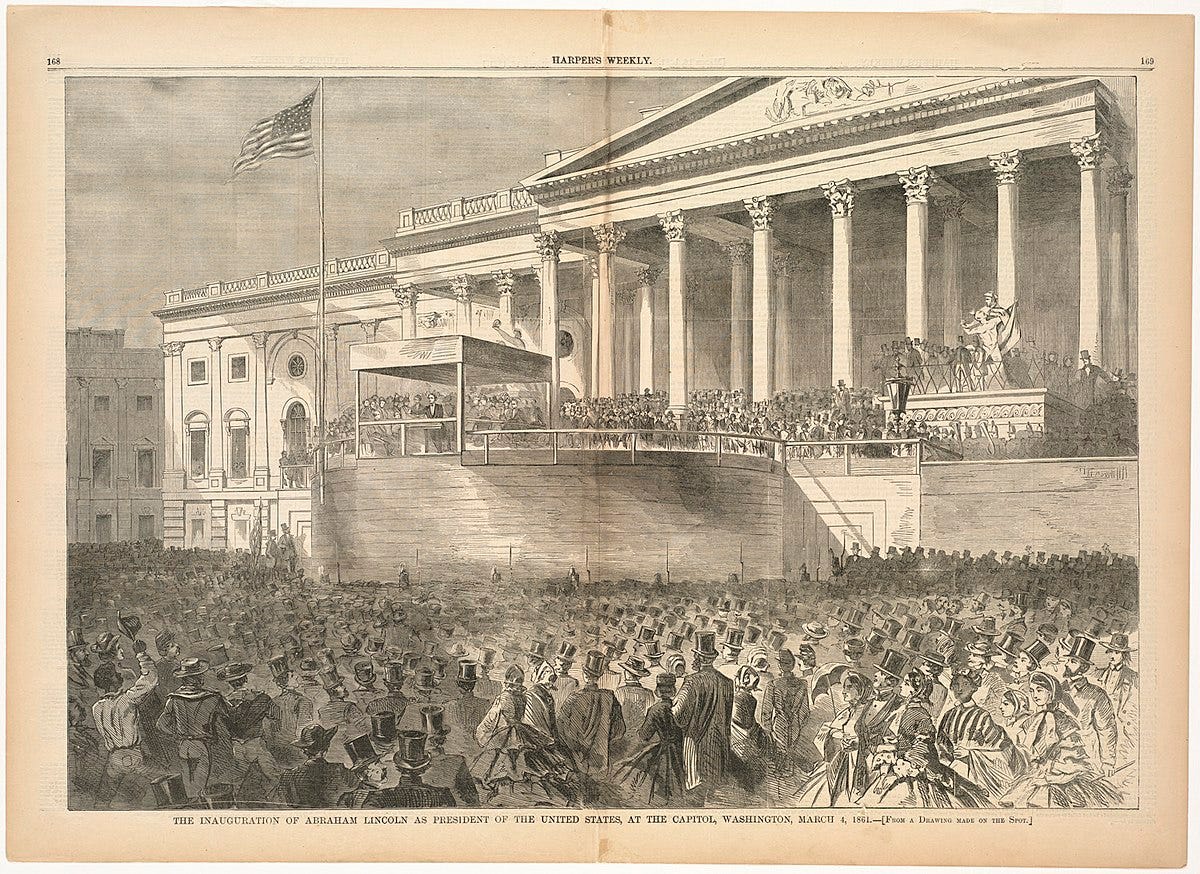

Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration in front of the under-construction Capitol, March 4, 1861, Winslow Homer, Harpers Weekly. Boston Public Library.

The final and most important argument for legislating preferences for classical architecture is its basis in objective truth. In mandating a specific architectural form, we are declaring that this form is better than another, and that we can make this decision based on rational and objective reasons. This belief is heretical in our current world. Modernism, and in particular Modernist architecture, is based on relativism. Our society has largely adopted the notion that beauty “is in the eye of the beholder,” and therefore we cannot and should not make any judgment claims on aesthetics. This approach is pervasive. Not only beauty has become subjective, but gender, marriage, and morality. The fight for objective truth can be held on the battleground of beauty, which unlike some other issues, is self-evidently objective.

Critics, on the other hand, argue that mandating classical styles for federal buildings would result in stagnated style stuck in the past. But they forget that classical architecture is based primarily on principles, not specific styles. Classical architecture includes certain universal features such as columns or pediments, but it has countless variations. The bill introduced by Republicans defines classical architecture as including diverse “styles such as Neoclassical, Georgian, Federal, Greek Revival, Beaux-Arts, and Art Deco.”

Giving preference to the classical style doesn’t require all new buildings to be replicas of the Capitol or the Supreme Court Building. Architects will be free to pursue countless varying styles and designs while restricting them to, as Jefferson said, a form of good “approbation.”

Designs for the courthouse in Anniston, Alabama, completed on budget and on time in 2022. General Services Administration.

And critics misunderstand our society’s current state. If Western culture was healthy and thriving, we probably would not need to regulate the federal building design; instead, we could trust our architects to build innovative and exciting new buildings which still rest on universal truths. Unfortunately, however, our architectural community has become consumed by Modernism and can no longer be trusted to pursue the good and beautiful.

Although unlikely to be passed by Congress and certainly doomed to be vetoed if it does, the precedent set by introducing laws which encourage and endorse architectural beauty is a positive step. We should continue to push federal, state, and local governments to fight back against the relativism that has produced so much aesthetic and moral ugliness in our world.

Stephen Sholl is a researcher at the Mathias Corvinus Collegium’s Architecture and Remembrance Center. He is an alumnus of Common Sense Society’s Carolina Fellowship and an active member of Common Sense Society–Hungary.