The Bloody And Heroic Origins Of Veterans Day

Veterans Day, originally Armistice Day, was instituted to commemorate those Americans who fought to end the Great War

Veterans Day honors all U.S. veterans, past and present, who served their country. But before 1954, it was known as “Armistice Day,” celebrating the end of the First World War and honoring those Americans who gave their lives to achieve victory.

While the British and Canadians still wear a red poppy on their Remembrance Day celebrations to recall the poppies of Flanders Field, there is no single episode of the First World War that captures the American imagination like the shock of Pearl Harbor, the heroism of D-Day, or the perseverance of the Battle of the Bulge. Yet for all that, America’s involvement in the First World War was just as crucial for victory as it was in the Second.

A Marine recruitment ad, James Montgomery Flagg, 1917. Wikimedia.

The conflict started, as the historian Christopher Clark describes it, with the opposing Allies and Central Powers “sleepwalking” into war, “watchful but unseeing, haunted by dreams, yet blind to the reality of the horror they were about to bring into the world.” When a Serbian nationalist assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian crown in the summer of 1914, he started a chain-effect that would trigger Europe’s complex alliance system and consume the world.

On one side was the Triple Entente, or the Allies: Great Britain, France and Russia. On the other was the Central Powers: Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. For years after the assassination, Europe was locked in a bitter stalemate. Gone were the heroic cavalry charges and wide flanking maneuvers of the Napoleonic era; now, trenches, massed artillery, and poison gas defined warfare. Millions of troops died, blown apart by shells or torn to shreds by machine gun fire, spilling their blood for mere handfuls of miles of enemy territory.

German soldiers attacking Dead Man's Hill near Verdun. Hermann Rex. Oberammergau/Wikimedia.

Germany’s use of unrestricted submarine warfare—most infamously, its sinking of the passenger ship the Lusitania, in which 128 Americans died—raised American anger, but for the first three years of European war the United States sat it out. The change came after the British cracked the Zimmerman Telegram, a German message suggesting an anti-American alliance with Mexico. Amid already growing anger, Congress decided the war seemed close to home.

But declaring war was one thing, and waging it was another. The U.S. was woefully unprepared for battle. It had never fought a major overseas war on this scale before. America also ran into major logistical and supply issues and had an army of only 127,151 men, dwarfed by Europe’s titanic militaries. In comparison, at its peak, the French had 8.3 million troops, with the other great powers usually matching or surpassing that number. The Germans had little esteem for the Americans, thinking them “a money hunting nation, too engrossed in the hunt of the dollar to produce a strong military force.”

A French flame attack on German trenches in Belgium. National Archives at College Park/Wikimedia.

But for all the problems the Americans faced, they were courageous and eager to jump into the fray. Just as importantly, they were fresh: at this point of the war, all the other combatants were bled white by fighting. By 1918, American troop numbers had grown to the point they could play a role in stopping the Spring Offensive, Germany’s last attempt to crush the Allies and end the war.

That fall, the Americans launched the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which was not only one of the biggest battles the U.S. ever fought (involving more than 1.2 million troops), but also the deadliest, with 26,277 Americans perishing. Though the U.S. forces faced well-entrenched German units, they were able to overcome the enemy positions. The Germans, for all their impressive defenses, were exhausted by four years of war, suffered from low morale, and were unable to stand up to the overwhelming American advance.

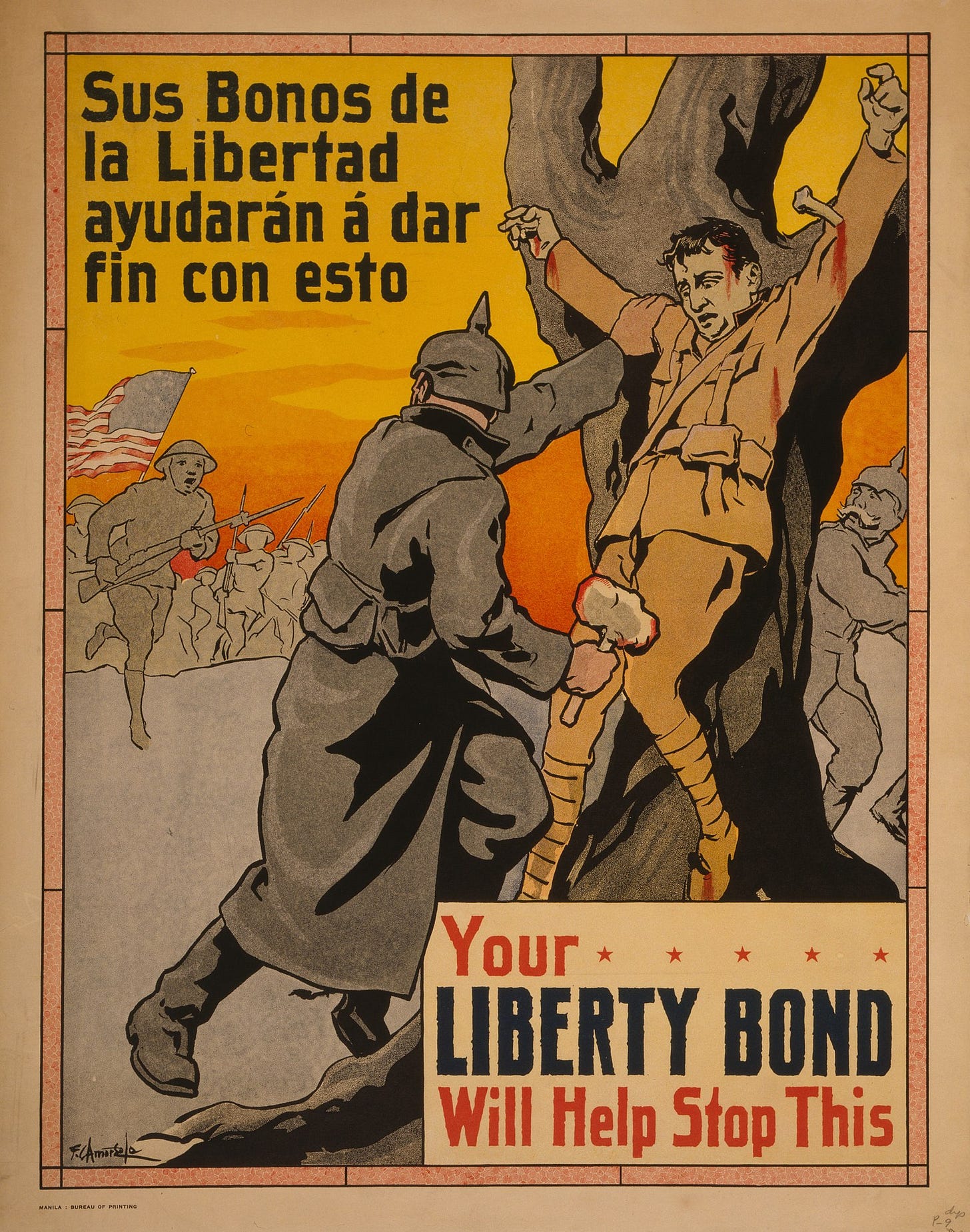

American Liberty Bond poster, 1917. Library of Congress/Wikimedia.

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive, along with other battles across the Allied line in the “Hundred Days Offensive,” led to the collapse of the German line. This massive defeat, following the failure of the German Spring Offensive and occurring at the same time as significant social unrest behind the German front lines, convinced Germany there was no more hope for victory. On November 11, 1918, the opposing sides signed an armistice. Though peace negotiations would continue into the next year, culminating with the Treaty of Versailles, the war was over.

Peace came at a terrible cost. Millions lay dead all over the world, including 116,708 Americans, and the seeds were already being sown for the Second World War. But for all the pain, the U.S. still played a major role in ending the Great War. Without American entry in the conflict, it is possible the war would have continued for months, adding to the tragic death toll.

French and American soldiers have a smoke, Leslie-Judge Company, January 1920. Wikimedia.

American soldiers proved themselves on the global stage, and they would do so again 23 years later when they battled and eventually defeated Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan–enemies far worse than the Central Powers. As we celebrate the sacrifice and heroism of our troops this Veterans Day, we should remember the origins of this holiday and give the American fighting man due credit for what he did to help gain victory in Europe 100 years ago.