By Aaron Rhodes

Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl’s life story is extraordinary. He was born in Vienna in 1905 and corresponded with Sigmund Freud as a teenager. As a young doctor in the 1930s, Frankl treated students threatening suicide. Following the 1938 Nazi takeover of Vienna, he was only permitted to work in a Jewish hospital, and was not allowed a formal medical title. The authorities forced his wife to undergo an abortion. Frankl had an exit visa that would have allowed him to escape deportation, but reflecting on the commandment to honor one’s parents, he allowed it to lapse. He was arrested in 1942 along with his parents, wife and siblings, and eventually incarcerated in four German concentration camps. His wife, parents, and brother did not survive.

Auschwitz concentration camp in 1945. Equipment abandoned by fleeing guards can be seen in the foreground. German Federal Archives.

In Auschwitz, in an astonishing example of will, detachment, and the assertion of freedom itself, Frankl continued his research along the lines he had begun before the war, documenting how inmates, whose lives already had meaning, often survived the concentration camps, when others did not. He helped them understand that despite daily “selections,” barbaric abuse, and the almost total lack of physical freedom in the camps, they still had choices: they could choose their response to the atrocities they faced. By thus exercising moral agency and choice they could retain their inner freedom and sense of purpose. After the war, Frankl resumed his professional career in Vienna. His book on Logotherapy has sold well over a million copies.

Frankl taught that choice was the “last freedom”--the freedom we can retain, regardless of circumstances. Religious freedom advocates, and many Americans, call it the “first freedom,” because the exercise of religious freedom allows us to form basic moral orientations that flow into all parts of our lives. Under the current, United Nations-sponsored, human rights dogma, it is taboo to call any human right more important than any other; all human rights have been officially declared equal, so religious freedom is considered no more important than the “human right” to taxpayer-funded employment counseling.

Virtually no one in the human rights establishment questions that absurdity. But Frankl’s work in psychology raises questions about human rights and freedom’s meaning. Regardless of what is done to us, we can retain our inner freedom to try to know and understand ultimate reality. So, are human rights really needed at all to protect intellectual and moral freedom?

The answer is yes. What coercion can do is impose itself on how we bring our actions into harmony with the universe’s moral order—what we make of our choices. Shortly after the emergence of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, Hannah Arendt wrote an essay that was eventually incorporated into the chapter on “The Decline of the Nation-State and the End of the Rights of Man,” in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951). Here she took up this question, evincing skepticism of an international human rights regime’s legitimacy—a skepticism likely informed by her efforts to save Jews deprived of citizenship, including herself. She explained that the French Revolution, which really launched the political internationalization of human rights, ultimately threatened their integrity by taking them out of the realm of the spiritual, and placing them into a purely political context—by the attempt to translate natural law into positive law. Arendt wrote that, “in the new secularized and emancipated society, men were no longer sure of these social and human rights which until then had been outside the political order and guaranteed not by government and constitution, but by social, spiritual, and religious forces…”

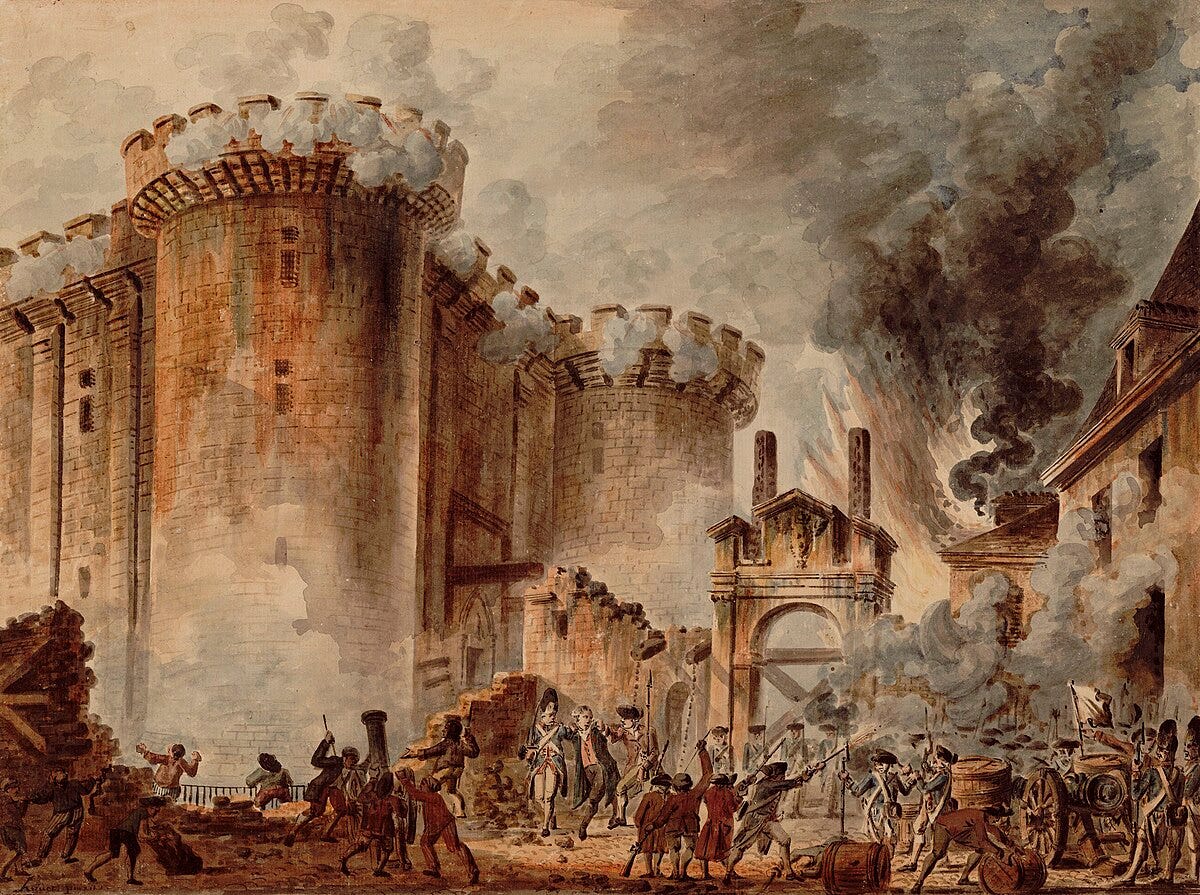

The Storming of the Bastille, Jean-Pierre Houël, 1789. National Library of France/Wikimedia.

She praised Edmund Burke’s criticism of the French “Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen.” Burke had countered, in Reflections on the Revolution in France, that human rights as proclaimed in that document were an “abstraction,” inferior to “inherited rights.” The source of law is “within the nation.”

Arendt said the notion of human rights that grew from the French Revolution “reckoned with an ‘abstract’ human being who seemed to exist nowhere,” and clarified that human rights can only be effectively preserved under national constitutions. She wrote that:

…the fundamental deprivation of human rights is manifested first and above all in the deprivation of a place in the world which makes opinions significant and actions effective…where treatment by others does not depend on what he does and does not do. This extremity, and nothing else, is the situation of people deprived of human rights. They are deprived, not of the right to freedom, but of the right to action; not of the right to think whatever they please, but of the right to opinion.

What is vital is the “right to have rights.”

Dr. Viktor Frankl debating at the University of San Diego during the 71-72 school year. University of San Diego.

The prose in Arendt’s famous book spills out almost as an intuitive stream of consciousness. She seems to confirm both the need for constitutional human rights protections, and the dangers human rights face from modern secular states, although prior to the modern world traditional human rights protections were scarce, and outside of British common law, legal ones basically nonexistent. People in Christendom could be certain that justice and their rights existed in the eternal spiritual realm, but they had few if any legal, worldly means to realize them. People in secular, liberal democratic societies have many rights, but their sacred foundations have been eroded.

The American Revolution gave societies a solution to what Arendt termed this “perplexity”: constitutional and legal rights based not on governments’ laws, but natural, inalienable rights grounded in ultimacy. The ideal of religious freedom so central to the United States’s establishment was not simply the freedom to believe, but to form and manifest communities of faith, and to take actions inspired by faith. To an extent like the French revolutionaries, America’s Founders also embraced what might be called universal, and thus “abstract” human rights, and America’s early human rights missionaries like Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson found their message of freedom taken up with alacrity by people in diverse societies who felt their natural rights abused. The United States is blessed with universal human rights protected by a national constitution; indeed, we have “a place…which makes opinions significant and actions effective.” We have, in Burke’s terms, “inherited rights” that are both particular to our land, culture and history, and universal, that is, a human rights tradition. That’s what is exceptional about the United States.

Aaron Rhodes is a senior fellow at the Common Sense Society, and president of the Forum for Religious Freedom-Europe.

Good read, thank you. This fusion of natural right with a national tradition is what America needs. Too often the two camps spend their days casting philosophical stones at one another instead of realizing their unity.