The Lesser-Known Battle That Saved Western Civilization

No Plataea, no Parthenon (and no Plato)

Roughly 2,500 years ago this week (the exact date is unknown), a united Greek force defeated the Persian army in the Battle of Plataea, forever ending the threat of Persian invasions to mainland Greece.

Fought close to Plataea, a city in the Boeotia region of central Greece (a province later known as the “dancing floor of Ares” due to the large number of historic battles fought there), the battle came at a hard time for the Greeks.

The Persians had defeated the Greek army at the Battle of Thermopylae and annihilated the Spartan rearguard of three hundred hoplites the previous year. Together with their legendary king, Leonidas, the Greeks had fought valiantly to the last man. The Persian King Xerxes followed this victory by annexing defenseless Athens and burning it to the ground.

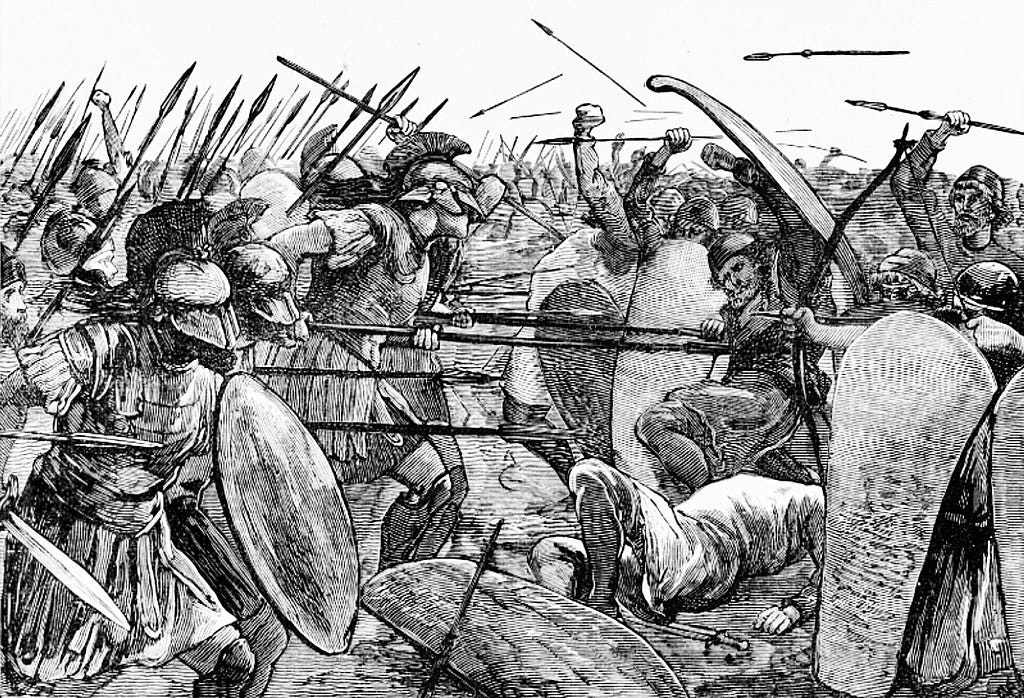

Greek Hoplites charge into battle. Georges Rochegrosse, 1859. Wikimedia.

But the Athenian defeat of the Persian fleet in the Battle of Salamis marked the war’s major turning point; in its aftermath, Xerxes retreated back to Asia with a large part of his forces.

But despite this stunning Athenian victory, the Persian occupation of northern Greece continued and a large Persian force under the general Mardonius remained in Boeotia. Even worse, disunity threatened to tear the Greek alliance apart: the Thebans had already allied themselves to the Persian invaders, and the battle-weary Athenians, who had borne the invasion’s brunt and watched their city burn, threatened the same if the other Greek city states refused to send aid quickly.

Athens’s entreaties worked. Their main ally, Sparta, sent a force of several thousand hoplites north to help their beleaguered allies.

But it wasn’t just the Spartans who came.

The Greek force that assembled at Plataea, which numbered tens of thousands of troops, was composed of hoplites from all over the Hellenic world—potentially one of the largest armies the ancient Greeks ever assembled, though the Athenians and Spartans had the strongest contingents. This was a remarkable feat for the land of Homer, which was made up of many city states that constantly fought among themselves.

The Greeks assembled in front of the Persian army, which, according to some estimates, numbered roughly an equal number of troops. The Greeks possessed the high ground and rebuffed Mardonius’ attempts to force them onto terrain where the Persians would have the advantage.

For days, Greeks and Persians faced each other in the hot August sun, neither side willing to meet the other in pitched battle. Mardonius’ cavalry launched multiple probing attacks on the Greek lines, harassing the army and attacking their supply lines.

When the Persian cavalry cut the Greeks off from their main freshwater source, the Greeks decided to retreat to a more defensible line. But the disorderly retreat caused the army’s wings to lose contact with each other.

Seeing this, Mardonius smelled blood. Not realizing the Greeks were simply seeking better defenses, he thought they were in full retreat, and attacked.

Spartans at Plataea. Cassell's Illustrated Universal History, Edmund Ollier, 1882. Wikipedia.

The Persians expected to face a disorganized rabble, but the Greeks, sensing the threat, rallied, turned around, and fought. The Persians found themselves facing a forest of spears instead of fleeing men. The Spartans faced the main Persian force on the right and the Athenians faced the Thebans, Persia’s Greek allies, on the left.

The Persians fought bravely but they were out matched. They were specialists in cavalry and archery, not toe-to-toe shock battle—precisely the area in which the Greeks excelled.

The bronze-clad Hellenic hoplites made short work of the Persian infantry. The Greeks steadily ground down their enemy and killed Mardonius. Their leader’s death led to a Persian rout. The Greeks then pursued the fleeing Persians to their fortified camp, breached the walls, and killed most of those who had survived the initial fighting.

The Greek victory was complete, and it wasn’t the only one. Around the same time as the Battle of Plataea (or even on the very same day, according to some sources), the Greeks landed an army in Mycale on Asia Minor’s coast and defeated another Persian army, as well as the remainder of the Persian fleet.

The History of Greece and Rome, including Judea, Egypt, and Carthage, by John Russell 1854. British Library/Wikimedia.

Over the next several decades, Athens led a coalition to attack Persian territory and liberate Greek city-states in Ionia, on Asia Minor’s western coast. But this campaign still lay in the future; the one-two punch of Plataea and Mycale ensured that Xerxes and his successors would abandon forever their ambition to conquer Greece.

Few of history’s battles match Plataea in importance. The aftermath of Persia’s retreat saw the beginning of Athens’s golden age, a time of cultural, artistic, and political flourishing. Athenian democracy matured during this period, and world-famous buildings like the Parthenon were erected. Some of the the world’s most famous and influential thinkers and artists—including philosophers like Plato, playwrights like Aristophanes and Euripides, and historians like Herodotus and Thucydides—wrote during this era.

Persian victory at Plataea would have made Greece a province administered from Persepolis. Very likely, Greek culture (and more specifically, Athenian culture) would have been stifled before it had the chance to flourish. The West as we know it would not have existed.

Many in our universities and in the media spend their time attacking the very foundations of the West, claiming there is little in our past we should be thankful for. But when we read Plato’s Republic, gaze on the the Parthenon’s beauty, or even appreciate democracy’s many benefits, we should gratefully remember the hoplites who united to face their enemies on the dancing floor of Ares more than two millennia ago.